Rapport d'information n° 481 (2016-2017) de MM. Éric BOCQUET , Michel BOUVARD , Michel CANEVET , Thierry CARCENAC , Jacques CHIRON , Philippe DALLIER , Vincent DELAHAYE , André GATTOLIN , Charles GUENÉ , Bernard LALANDE et Albéric de MONTGOLFIER , fait au nom de la commission des finances, déposé le 29 mars 2017

Disponible au format PDF (2,4 Moctets)

Synthèse du rapport (603 Koctets)

-

FOREWORD

-

SUMMARY OF THE MAIN PROPOSALS

-

OVERVIEW: THE BLURRED LINES OF TAXATION AND SOCIAL

CONTRIBUTIONS RULES GOVERNING ONLINE PLATFORM USERS

-

I. AS REGARD TAXATION, ALL INCOME IS TAXABLE FROM

THE FIRST EURO WITH VERY FEW EXCEPTIONS

-

II. AS REGARDS SOCIAL CONTRIBUTIONS, THE PROBLEM

LIES IN THE DISTINCTION BETWEEN PRIVATE INDIVIDUALS AND PROFESSIONALS

-

A. AMONG PLATFORM USERS, MANY PROFESSIONALS ARE

UNAWARE OF THEIR STATUS

-

B. TWO THRESHOLDS FOR COMPULSORY AFFILIATION TO

SOCIAL SECURITY CREATED IN 2017: A USEFUL YET INCOMPLETE STEP FORWARD

-

C. CORPORATE LAND PROPERTY TAX, A TAX THAT APPLIES

TO ALL PROFESSIONAL WORKERS

-

D. SOCIAL LEVIES, THE FORGOTTEN PART OF THE

DEBATE?

-

A. AMONG PLATFORM USERS, MANY PROFESSIONALS ARE

UNAWARE OF THEIR STATUS

-

III. REPORTING, CONTROL AND COLLECTION:

-

A. SELF-REGULATION: AN ENCOURAGING YET INHERENTLY

LIMITED RESPONSE

-

B. UNACHIEVABLE TAX CONTROL

-

C. THE OBLIGATION OF USER INFORMATION: A FIRST STEP

TOWARDS TAX COMPLIANCE

-

D. AUTOMATIC INCOME REPORTING: THE DECISIVE

STEP?

-

A. SELF-REGULATION: AN ENCOURAGING YET INHERENTLY

LIMITED RESPONSE

-

I. AS REGARD TAXATION, ALL INCOME IS TAXABLE FROM

THE FIRST EURO WITH VERY FEW EXCEPTIONS

-

PROPOSALS: EXEMPTING SMALL TRANSACTIONS BETWEEN

PRIVATE INDIVIDUALS, ENSURING FAIR TAXATION OF PROFESSIONALS

-

I. A SINGLE THRESHOLD OF EUR 3,000 PER YEAR TO

EXEMPT LOW, OCCASIONAL AND SIDELINE INCOME OF INDIVIDUALS

-

A. THE CHOICE OF A FIXED TAX ALLOWANCE

-

B. A SYSTEM THAT ECNOURAGES THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE

SHARING ECONOMY, WITHOUT A THRESHOLD EFFECT OR A DISTORTION OF

COMPETITION

-

C. JUSTIFICATION OF THE AMOUNT OF EUR 3,000

-

D. OBSERVATIONS REGARDING PROPORTIONALITY AND

OTHER CONSTITUTIONAL PRINCIPLES

-

1. The principle of a single threshold is in line

with the objective of accessibility and intelligibility of the law

-

2. The limitation of the advantage to income

derived from platforms and reported automatically is in line with the objective

of combating tax fraud and tax evasion

-

3. A measure general interest ground, with no

alternative in the short term

-

1. The principle of a single threshold is in line

with the objective of accessibility and intelligibility of the law

-

A. THE CHOICE OF A FIXED TAX ALLOWANCE

-

II. AN ALIGNMENT OF SOCIAL PROTECTION

OBLIGATIONS

-

A. A SIMPLE AND UNIQUE CRITERION FOR

DISTINGUISHING PRIVATE INDIVIDUALS FROM PROFESSIONALS

-

1. Presumption of non-affiliation to Social

security as a self-employed worker when income is less than EUR 3,000 per

year

-

2. A criterion with no effect on the equality of

treatment and the requirement of fair competition between professionals

-

3. Towards other maximum social contribution

thresholds?

-

4. Towards a collaborative worker status -

eventually?

-

1. Presumption of non-affiliation to Social

security as a self-employed worker when income is less than EUR 3,000 per

year

-

B. THE REMOVAL OF SECTOR-SPECIFIC OR GENERAL

LIMITATIONS BELOW THE EUR 3,000 THRESHOLD

-

A. A SIMPLE AND UNIQUE CRITERION FOR

DISTINGUISHING PRIVATE INDIVIDUALS FROM PROFESSIONALS

-

III. AUTOMATIC INCOME REPORTING: SIMPLIFYING

PROCEDURES AND SECURING TAX COLLECTION

-

A. A VIRTUOUS CIRCLE: VOLUNTARY REPORTING WITH AN

INCENTIVE

-

B. DETAILS ABOUT THE AUTOMATIC REPORTING

PROCEDURE

-

1. The user's prior explicit agreement

-

2. Content of the report: only available, relevant

and strictly necessary information

-

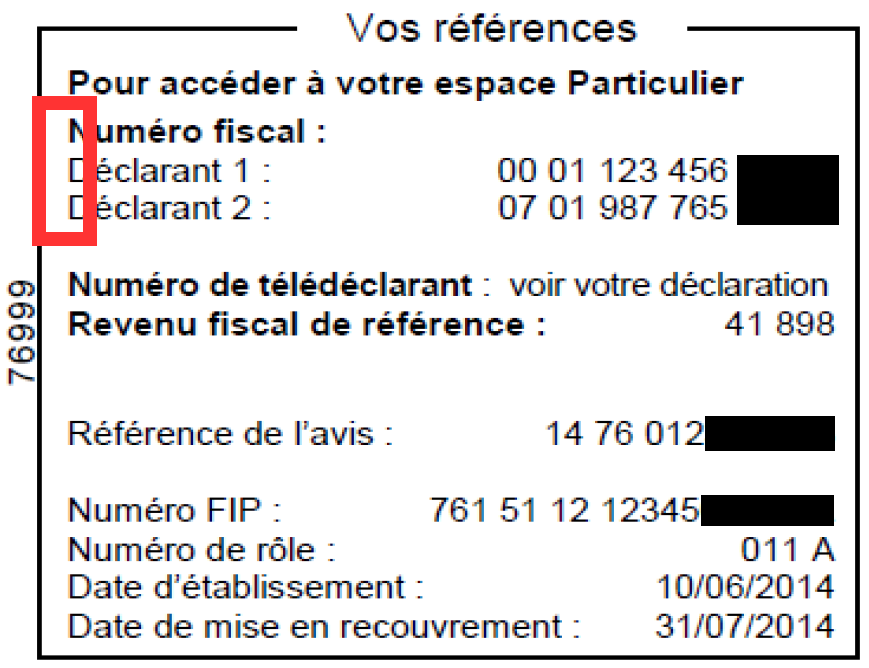

3. Unique identification number or tax

identification number?

-

4. High level of data protection

-

5. Technical implementation: the requirement of

simplicity

-

6. The particular case of income exempt by nature

and the creation of an online platform ruling

-

1. The user's prior explicit agreement

-

C. THE LEVY AT SOURCE OF INCOME TAX BY THE

PLATFORMS: NOT A VIABLE SOLUTION AT THIS STAGE

-

D. A PREREQUISITE: ENSURING PLATFORM

CERTIFICATION AND PROPER USER INFORMATION

-

E. TAX CONTROL: NEW PRIORITIES AND UPGRADED

TOOLS

-

A. A VIRTUOUS CIRCLE: VOLUNTARY REPORTING WITH AN

INCENTIVE

-

I. A SINGLE THRESHOLD OF EUR 3,000 PER YEAR TO

EXEMPT LOW, OCCASIONAL AND SIDELINE INCOME OF INDIVIDUALS

-

INTERNATIONAL COMPARISONS: SINGLE THRESHOLD AND

AUTOMATIC REPORTING, A CHOICE MADE BY SEVERAL COUNTRIES

-

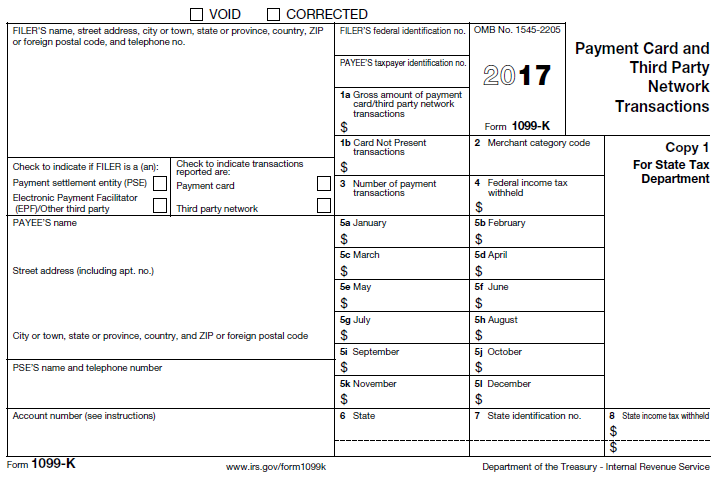

I. THE UNITED STATES: INCOME IS REPORTED TO THE

FEDERAL AUTHORITIES AND SOMETIMES TO LOCAL AUTHORITIES

-

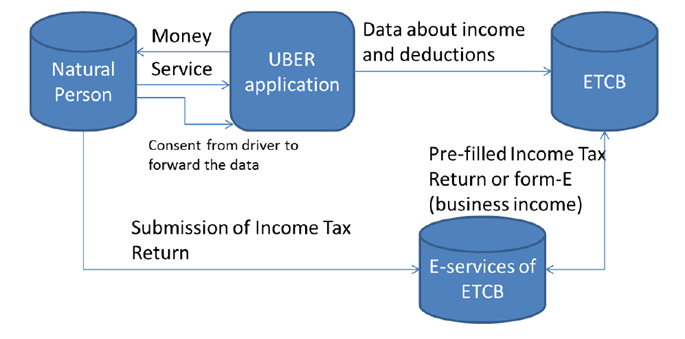

II. ESTONIA: A DEAL WITH UBER FOR AUTOMATIC

REPORTING OF DRIVERS' INCOME

-

III. THE UNITED KINGDOM: A VERY ATTRACTIVE

TAXATION REGIME, WITH NO DECLARATIVE OBLIGATIONS IN RETURN

-

IV. BELGIUM: A VIRTUOUS MECHANISM, YET CURRENTLY

LIMITED TO SOME INCOME CATEGORIES ONLY

-

V. ITALY: AN INCENTIVISING SYSTEM, WHICH REMAINS

TO BE ADOPTED

-

I. THE UNITED STATES: INCOME IS REPORTED TO THE

FEDERAL AUTHORITIES AND SOMETIMES TO LOCAL AUTHORITIES

-

WORKING GROUP HEARINGS

N° 481

SENATE

ORDINARY SESSION 2016-2017

|

Registered at the Senate's Presidency on 29 mars 2017 |

REPORT

MADE

in the name of the finance committee(1) on taxation and the collaborative economy : the need for a fair, simple and unified system.

By Messrs Éric BOCQUET, Michel BOUVARD, Michel CANEVET, Thierry CARCENAC, Jacques CHIRON, Philippe DALLIER, Vincent DELAHAYE, André GATTOLIN, Charles GUENÉ, Bernard LALANDE and Albéric de MONTGOLFIER,

Senators

|

(1) This committee is composed of : Ms Michèle André , chair ; Mr Albéric de Montgolfier , general reporteur ; Ms Marie-France Beaufils, Messrs Yvon Collin, Vincent Delahaye, Ms Fabienne Keller, Marie-Hélène Des Esgaulx, Messrs André Gattolin, Charles Guené, Francis Delattre, Georges Patient, Richard Yung , vice-chairs ; Messrs Michel Berson, Philippe Dallier, Dominique de Legge, François Marc , secretaries ; Messrs Philippe Adnot, François Baroin, Éric Bocquet, Yannick Botrel, Jean-Claude Boulard, Michel Bouvard, Michel Canevet, Vincent Capo-Canellas, Thierry Carcenac, Jacques Chiron, Serge Dassault, Bernard Delcros, Éric Doligé, Philippe Dominati, Vincent Éblé, Thierry Foucaud, Jacques Genest, Didier Guillaume, Alain Houpert, Jean-François Husson, Roger Karoutchi, Bernard Lalande, Marc Laménie, Nuihau Laurey, Antoine Lefèvre, Gérard Longuet, Hervé Marseille, François Patriat, Daniel Raoul, Claude Raynal, Jean-Claude Requier, Maurice Vincent, Jean Pierre Vogel . |

FOREWORD

The collaborative economy is now part of everyday life for millions of people in France: they buy and sell on Leboncoin , travel with Blablacar , rent out their car on Drivy , their toddlers buggy on Zilok and their DIY skills on Stootie . Some are genuine professionals, like private hire (VTC) drivers or graphic designers on Hopwork .

This new economy, which provides numerous opportunities for exchanges between people and blurs existing lines, has always given the impression that it was developing outside any legal framework. However recent events such as UberPop being shut down, Heetch being interrupted or Airbnb's problems in Paris, have reminded us that this is not the case. More specifically, when it comes to taxation and social contributions, legal rules do exist .

With regard to taxation, there is no such thing as a grey areaontrary to what many users tend to believe, all income is taxable from the first euro, whatever its origin or amount, and regardless of whether it is occasional or from a sideline activity. Moreover, although most situations fall under ordinary law, some categories of income are actually subject to specific taxation regimes - which are often complex and outdated, and of which people are generally unaware.

There are only two exceptions. First, second-hand sales are generally not subject to tax - but their definition is imprecise. Second, cost-sharing, but it is defined in a very restrictive way - for example, it applies to ridesharing, but not to a family who rents out their car occasionally to cover their expenses.

As regards social contributions, on the contrary, this is a grey area, because there are no simple and objective criteria for distinguishing private individuals from professionals. There are no minimums in terms of income amount, time or frequency, meaning that a few hours of babysitting per month, or selling a few "hand-madejewellery items online, may result in compulsory affiliation to the self-employed social security regime ( Régime social des indépendants - RSI ) which comes together with the payment of social contributions and professional taxes, the obligation to attend a qualification course, to comply with health and safety standards, etc.

All these rules were designed for exchanges in a physicalworld, a world of week-end car boot sales, flea markets and minor services between neighbours. But in practice, no one actually questioned these rules because they were not enforced. The amounts at stake were low, and the controls were sparse.

Now that trading between private individuals has become massive, standardized, and traceable, it is no longer possible not to ask the question. On the one hand, if existing rules were enforced, they would discourage many private individuals and would deal a heavy blow to the sharing economy and its ecosystem. On the other hand, because they are not enforced, they allow widespread abuse, with fake” private individualswho avoid paying their taxes and social obligations and create both a distortion of competition and a loss of tax revenue.

On 29 March 2017, the Working Group of the Finance Committee of the French Senate on taxation of the digital economy, a non-partisan, collegial and informal subcommittee, presented a bill to establish a simple, unified and fair taxation regime for the collaborative economy 1 ( * ) . This regime, encompassing both taxation and social contributions, would be based on a single threshold of EUR 3,000 per year, known to all.

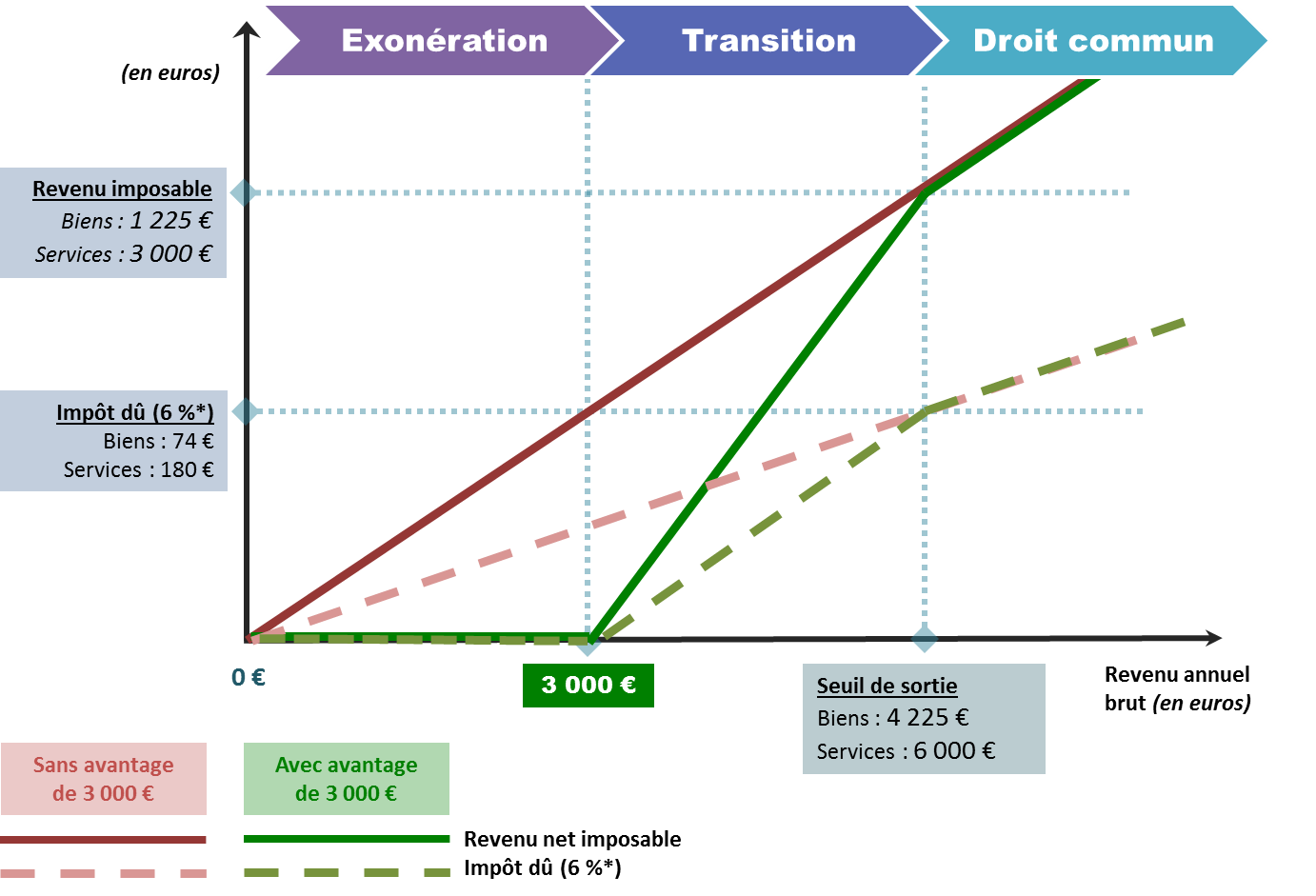

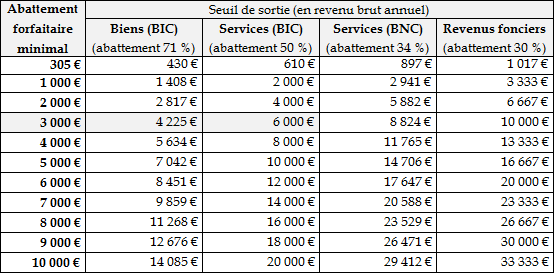

As regards taxation, it would allow an exemption of low, sideline and additional income received via online platforms. The advantage would then be regressive for higher income, ensuring that any person receiving significant income from online sources would be treated strictly equal to professionals in the physicalworld.

As regards social contributions, the threshold of EUR 3,000 would - at last - provide a criterion to distinguish between a private individual and a professional: under this threshold, it would never be compulsory to join the social security regime as a self-employed worker. Belgium and the United Kingdom also chose the simplicity of a threshold-based system.

In return for these benefits, the user would be required to accept that the platform automatically reports his income to the tax administration: this is not only a means of ensuring the fairness of treatment between all taxpayers, but it is also a service and a simplification of the procedures. This system exists in Estonia, where it has proved very successful.

In practice, the very large majority of users of collaborative economy platforms would actually be exempted from income tax thanks to the EUR 3,000 allowance - as everyone can see on the online simulator on the Senate website 2 ( * ). Moreover, everything that is exempted today (second-hand sales, car sharing, etc.) would remain so in the future, even for amounts greater than EUR 3,000. The measure does not create any new tax.

The bill also aims to change a number of obsolete rules, such as the maximum limit of two car boot sales per year and per person, or the obligation for public servants to obtain a written agreement from their authority to undertake a secondary activity two rules that seem totally unadapted to digital habits

It appears that many of the actors consulted by the Working Group welcomed those proposals, and among them digital platforms but also traditional professions. In fact, all of them ask for the same thing: a set of fair and simple rules, that are actually enforced.

This is what this report and the resulting bill are about: herein lies an opportunity that must not be missed.

SUMMARY OF THE MAIN PROPOSALS

|

Proposal No. 1 Establish a fixed tax allowance of EUR 3,000 on all income received by individuals via online platforms and automatically reported by these platforms, so that occasional and sideline income can be exempted with a simple rule. For amounts above EUR 3,000 of gross income, the tax advantage would be regressive, and would become neutral when the income becomes significant. |

|

Proposal No. 2 Establish a simple and unique criterion for distinguishing private individuals from professionals, with regard to social contributions, based on the same threshold of EUR 3,000 of gross income. If their income from online platforms is below this threshold, users would be presumed non-professional, and therefore not affiliated to the social security regime of self-employed workers, and not subject to social contributions. |

|

Proposal No. 3 Establish a presumption of supervisor's agreement for public servants who carry out a sideline activity via an online platform, and who do not earn more than EUR 3,000 per year from this activity |

|

Proposal No. 4 Allow the rental of movable property between individuals (cars, accessories, etc.), in particular via the Internet, to be taxed under the micro-BIC regime (for industrial and commercial profits). This practice is already tolerated by doctrine and case-law. |

|

Proposal No. 5 Remove the formal constraints on second-hand sales between private individuals, in particular the maximum limit of two sales per year and the production of a sworn certificate, when these sales take place on a duly certified online platform. |

|

Proposal No. 6 Publish a tax instruction to clarify and simplify the distinction between second-hand sales and commercial sales, on the model of the tax instruction of 30 August 2016 relating to co-consumption activities. |

|

Proposal No. 7 Make automatic income reporting the sine qua non condition to benefit from the EUR 3,000 tax advantage. The system would then be voluntary, simple and reliable, and would work as an incentive. |

|

Proposal No. 8 Allow online platforms to request from the tax administration, on a voluntary basis, an advance validation of their internal rules and procedures aimed at determining whether their users' income is taxable or not (online platform ruling |

|

Proposal No. 9 For users under micro-entrepreneur status, and with their agreement, allow the platforms to collect not only social contributions, but also the flat tax discharging the payment of income tax. |

|

Proposal No. 10 Make platform certification a real label, indicating to users that they comply with tax rules. For this purpose, the certificate should be displayed on the platform homepage in a visible position, and should mention its date of obtention and the reference of the certifying third party. |

|

Proposal No. 11 Publish, by late 2017, guidelinesfor platform certification, in order to set high quality standards for both the content of the certificate and the certification process, and encourage the application of best practices by certifying third parties. |

|

Proposal No. 12 Adapt the obligation of user information on platforms to the diversity of their business models. When very frequent, similar micro-transactions are performed (click adverts, videos according to the number of views), platforms should be exempted from the obligation to provide information each time a transaction is concluded |

|

Proposal No. 13 Exempt online platforms offering activities which are non-taxable by nature (such as cost-sharing) from the obligation to send an annual summary of transactions to each of their users. To be exempted from this obligation, platforms would have to implement duly certified internal processes guaranteeing the non-taxable nature of the income generated by the activities. |

|

Proposal No. 14 Strengthen tax audit capacities and give priority to audits of platforms and users who do not opt for automatic income declaration. |

|

Proposal No. 15 Create a request for information regime at the European Union level, allowing tax authorities to send non-nominative requests to the platforms. |

|

Proposal No. 16 Allow the tax administration to develop advanced skills in data analysis, in particular by offering remunerations attractive to high level profiles. |

|

Proposal No. 17 Produce an annual study on the main figures of the online platform economy and their users' income. This study should be transmitted to the Parliament and should be supplied in particular with information collected from automatic income reporting. |

|

Proposal No. 18 Promote a common approach at the European or international level for adapting taxation rules to the online platform economy, for example through the publication of guidelinesby the European Commission or the OECD. |

I

OVERVIEW: THE BLURRED LINES OF TAXATION AND SOCIAL CONTRIBUTIONS RULES GOVERNING ONLINE PLATFORM USERS

The Collaborative Economy, or Online Platform Economy, is not just a momentary fashion, but a long-term trend .

According to a study by PwC covering nine European countries, 275 platforms and five key business sectors 3 ( * ) , in 2015 it accounted for around 28.1 billion euros of transactions in Europe , an amount which almost doubled in just one year (15.9 billion euros in 2014), and which could reach 572 billion euros by 2025, a twenty-fold increase .

This same study estimates that on average, 85% of the value of transactions facilitated by the platforms is received by the user the remainder being split between the commission charged by the platform and insurance, etc.

|

What is an online platform? Since the Act of 7 October 2016 for a Digital Republic 4 ( * ) , online platforms have a definition in domestic law, which is contained in Article L. 111-7 of the Consumer Code: An online platform operator is any natural or legal person offering, on a professional basis, for free or in return for payment, an online communication service to the public based on: 1. Classifying or referencing content, goods or services by means of computer algorithms offered or put online by third parties; 2. Or facilitating the establishment of contacts between several parties for the purpose of the sale of a good, the provision of a service or the exchange or sharing of an item of content, a good or a service. Collaborative platformsare mainly in the second category, i.e. they are platforms for establishing contacts , organising a virtual marketplace where buyers and sellers meet. However, in this report, the term online platformsis generally preferred to that of collaborative platforms , which has no legal definition in French law. |

However, by creating new opportunities for exchanges and services for millions of people, by blurring the boundaries between private individuals and professionals and between regular activities and occasional ones, the collaborative economy challenges the very foundations of our tax and social contribution system .

For platforms whose sellers or service providers are exclusively professionals, regardless of whether they are self-employed or employees 5 ( * ) , the existing law applies with no particular problem. The same is true for platforms offering exclusively non-profit activities, even if this condition is sometimes harder to establish (cf. below).

However, very often, platforms bring together both private individuals and professionals in mixedmodels, where distinguishing between the two is not always possible it being understood, moreover, that the status displayed or requested on the platform does not imply that the income received is subject to tax and social contributions. Beyond the diversity of economic models, online platforms can be grouped into five broad categories, all of them bringing together, although each time in different proportions, private individuals and professionals as well as paid and unpaid activities.

|

Online platforms: a few examples Service platforms . Specialising in services to individuals (DIY, gardening, sports coaching, babysitting, home tutoring, etc.), Stootie has 800,000 users , ranging from private individuals looking to supplement their income to skilled craftsmen using it as one way of carrying out their business. Conversely, the 42,000 self-employed workers registered on Hopwork are qualified professionals, who all have a verified status (micro-entrepreneur, sole trader, etc.), and offer companies consultancy missions in marketing, communications, graphics and software development. 90% have chosen to be self-employed, in particular, for 31% of them, in order to earn more. Rental platforms . Cars are the items most frequently rented on collaborative platforms in Europe in particular on such French sites as Drivy , Ouicar and Koolicar . Apart from cars, Zilok has 350,000 objects of all types for rental between individuals and professionals , divided into 700 categories: tools, audio/video equipment, household appliances, suits, luxury accessories, holiday homes and musical instruments. |

|

Hosting platforms . Taking the Airbnb platform by itself, the platform carried 350,000 advertisements in France in 2016, against 7,000 advertisements in 2012. Paris, the leading world destination of Airbnb , carried 85,000 advertisements (60,000 of which within the city boundary). The adverts are place both by individuals and professionals (agencies). Mobility platforms . In France, 40% of 18-35-year-olds are signed up on Blablacar , a car sharing platform which, by definition, is targeted at individuals looking to share their expenses. At the other end of the spectrum, apps such as Uber , LeCab and Private Driver offer transport services carried out by professionals who hold a private hire driver or internal transport (LOTI) licence . Goods sales platforms . These marketplaces are used by both professional sellers and individuals, and do not always distinguish second-hand sales from sales of a commercial nature. They are not always payment service providers. On the main one, Leboncoin , 18.5 million people in France bought or sold a good in 2016, almost 100 million transactions and for a total amount of 21 billion euros . We can also mention the auction platform eBay , and specialised platforms, such as Vide Dressing for second-hand clothes and accessories and A Little Market , specialised in hand-madeobjects. Source: Senate Finance Committee, according to the above-mentioned PwC study and information communicated or published by the various platforms |

The annual income of the users of online platforms is often modest : 350 euros on Stootie , 700 euros on Drivy and Ouicar etc. Excluding real estate and vehicles, individual sellers earned an average of 396 euros on Leboncoin in 2016, an amount equal on average to 3.5% of their total income, and most people using this small ads site are private individuals. The amount of these earnings can however be quite significant: a mission on Hopwork brings in 2,000 euros on average, an amount which is more or less equal to the income of a typical hoston Airbnb , with these average amounts hiding wide disparities.

This new economy has long given the impression of developing outside the law, in particular as regards taxation and social contributions . A succession of events however has changed things considerably the closure of UberPop , the problems with Airbnb in Paris, the recent suspension of Heetch but also the success of platforms such as Blablacar and Drivy which now require a clarification of the rules.

Today, people are starting to become aware of the situation: rules do exist but they are very largely unsuited to the digital economy.

I. AS REGARD TAXATION, ALL INCOME IS TAXABLE FROM THE FIRST EURO WITH VERY FEW EXCEPTIONS

On 2 February 2017, the Ministry of Economy and Finance published 6 ( * ) a document entitled Income derived from online platforms or self-employed activities: what must be declared? How? ” This document, which is annexed to this report, contains five explanatory sheets , regarding the tax and social contribution obligations applicable to income stemming respectively from car sharing, renting out furnished accommodation, the sale of goods, the rental of goods and paid services.

First of all, the publication of these explanatory sheets should be welcomed since they are the first attempt to make a general presentation of the tax and social contribution rules applicable to users of collaborative platforms .

However, in their attempt to “explain”, what these sheets have demonstrated above all is the very great complexity of the existing rules and how unworkable they are . Instead of answers in full, comforting for all, clear, intelligible and fair heralded in the editorial which precedes the sheets, any users who read them will instead only find confirmation that:

- on the one hand, there is no area of tolerance as far as taxation is concerned: all income must be declared and is subject to income tax , with the exception of second-hand sales, whose definition is unclear, and co-consumption, activities, a new category whose scope is much narrower than that of exchanges between individuals. In addition, many dispensatory arrangements may apply;

- on the other hand, there is uncertainty as to the distinction between private individuals and professionals with regard to social contributions , so that many private individualsare in fact self-employed workerswho are unaware of this fact and who should join the self-employed workers system (RSI),), pay social contributions and comply with many sector-specific obligations as regards qualifications, certifications, health and safety regulations etc.

Devised for a physicalworld in which they remained mostly ignored as far as exchanges between individuals were concerned, these rules have now come face to face with the social and economic reality of the online platform economy.

In fact, the ministers, in the editorial that precedes the explanatory sheets say as much: We are aware that unlike professionals, those individuals who develop a sideline activity do not necessarily have the right reflexes in relation to regulatory, tax and social protection matters; these are complex subjects and it is important to provide them with support . During the hearings conducted by the Working Group, it not only became apparent that very many users of platforms were, in good faith, unaware of all or some of these rules, but also that the authorities themselves had, only when drafting the explanatory sheets, realised just how complex the subject is.

In reality, the process of clarification undertaken in the past few months, while commendable in its intention, could only run into the problem of the governments choice to explainthe situation as it stands, to stick to existing rules, on the grounds that there is no reason to apply specific rules to one source of income compared to another just because it is received via online platforms this is the main thrust of the title of the document published on 2 February 2017, which mentions without differentiating them income derived from online platforms and from self-employed activities . This unwavering position has several times led the Government to turn down the proposals of the Working Group, in particular when discussing the Finance Bill for 2016, even though they had been adopted by a very large majority in the Senate.

Equally unwaveringly, the Working Group believes that there is good reason to change the rules applicable to income derived by private individuals from their sideline and occasional activities, or at the very least to those that they carry out via online platforms, because these old and complex rules are not suited to exchanges between individuals on the Internet , which have near to nothing in common with those of the physicalworld, in terms of volume, form and participants. Hence:

- they are therefore not enforced , which allows certain individuals to receive substantial income, while not meeting their tax and social contribution obligations, which leads to a situation of unfair competition in respect of the other professionals ;

- if they were strictly enforced , which is not the case, on the contrary they would put very many private individuals in an uncomfortable position , in particular the unemployed with few prospects, persons on low income or simply amateurs or enthusiasts, and this would simply threaten the economic model of many collaborative platforms .

Before setting out in detail the proposals of the Working Group, the explanations below show the current rules and why they are not applied.

A. INCOME RECEIVED VIA ONLINE PLATFORMS DOES NOT BENEFIT FROM ANY SPECIAL TREATMENT

Income received by private individuals for their activities carried out via online platforms is subject to the same taxation rules as their other categories of income . In particular, they are subject to income tax in accordance with Article 12 of the General Tax Code (Code Général des Impôts - CGI ) , which provides that the tax is payable each year on the profits or income that the taxpayer makes or from which he benefits in the course of the same year .

Occasionalor income does not therefore benefit from any special treatment , whatever its origin and whatever the amount. Therefore, amounts received via online platforms are in principle taxable from the first euro, and must be declared in line with the provisions of ordinary law .

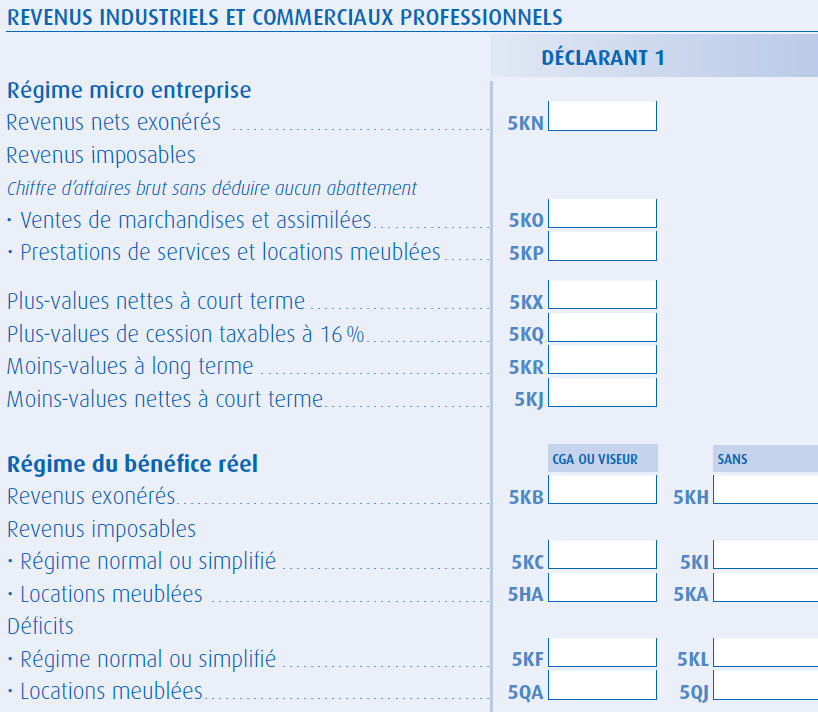

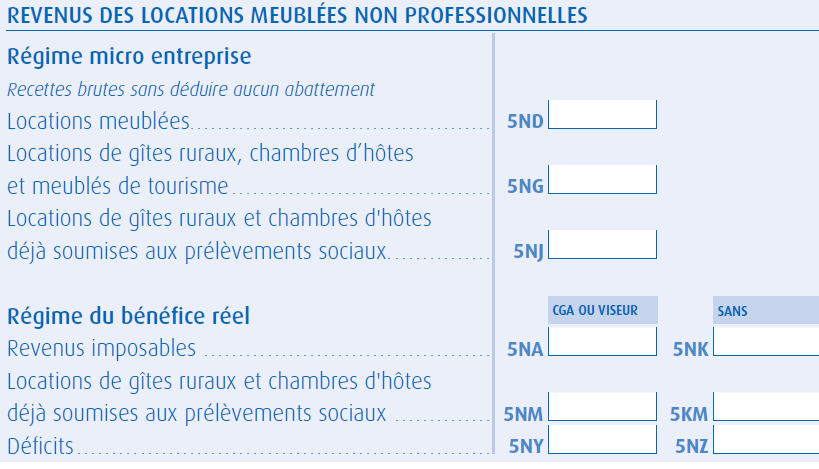

These categories are profits and capital gains from self-employed workers which generally fall in the category of industrial and commercial profits ( Bénéfices Industriels et Commerciaux - BIC), non-commercial profits ( Bénéfices Non-Commerciaux - BNC) or real estate income , whether or not they derive from professional activities within the meaning of the Social Security Code (see below).

|

Self-employed workersincome Industrial and commercial profits (BIC) are defined by Article 34 of the General Tax Code as profits made by natural persons derived from the exercise of a commercial, industrial or craft occupation . Article L. 110-1 of the Commercial Code 7 ( * ) deems commercial transactions 8 ( * ) to be the following activities, widespread on online platforms: 1° Any purchase of movable property for resale , either in its original condition or after having transformed and used it; [] 4° Any rental of movable property business ; 5° Any manufacturing, agency, land or water transport business; [] 7° Any exchange, banking or brokerage transaction, issuance and management of electronic money and any payment service 9 ( * ) . Non-commercial professional profits (BNC) are, under the terms of Article 92 of the General Tax Code, profits from liberal professions, from responsibilities and offices whose holders do not have trader status and from all occupations, lucrative operations and sources of profits distinct from another category of profits or income . Liberal professions are those in which the intellectual activity plays the main role and which comprise the personal practice of a science or an art for example, with regard to platforms, school work or guitar tuition at home, but also the creation of a logo, a website or a translation. People with this status carry out their business fully independently which distinguishes them from employees and their property and actions are, in principle, governed by civil law, which distinguishes them from traders. Source: Finance Committee of the Senate |

The beneficiaries of these categories of income have the choice between being taxed on the basis of their real income and charges or on the basis of the “micro-tax” system , often preferable because simpler and more suited to occasional activities. Subject to annual turnover not exceeding the VAT exemptionthresholds provided for by Article 293 b of the General Tax Code, i.e. EUR 82,200 or EUR 32,900 depending on the activities, they can benefit from a proportional tax-free allowance on their annual gross income, which takes into account, in a simplified way, expenses incurred for the activity . These tax-free allowances are:

- 71% for micro-BIC sales of goods 10 ( * ) ;

- 50% for micro-BIC services 11 ( * ) in the case of a commercial or craft activity;

- 34 % for micro-BNC services 12 ( * ) , if a science or an art is exercised;

- 30% for unfurnished rentals under the micro real estate system 13 ( * ) .

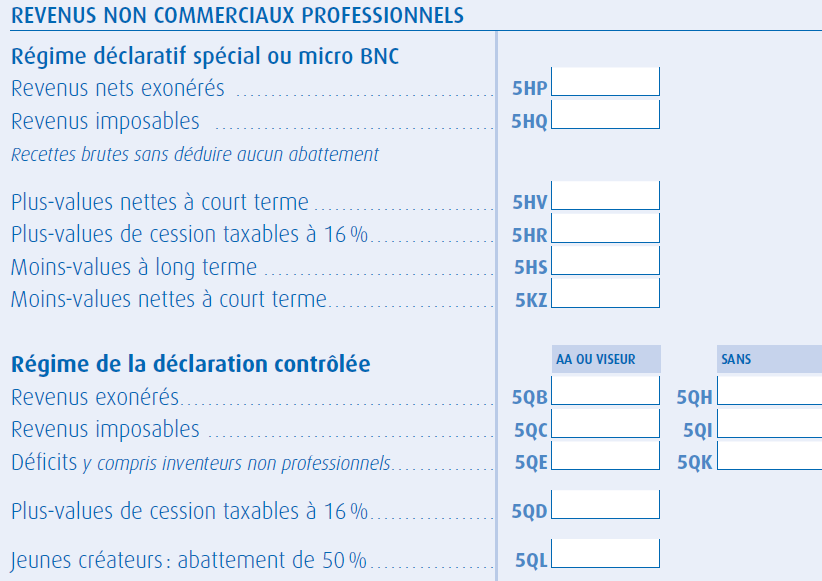

With regard to the declarative procedures , taxpayers who are covered by the micro-tax system need only to state their gross proceeds on the supplementary declaration form No. 2042 C PRO (see below). The tax authority then applies the proportional “tax allowance” and calculates the amount of tax due according to the progressive tax rate under ordinary law conditions.

The micro-tax system: summary

|

Micro-tax system |

Examples |

Tax allowance |

Maximum gross income |

|

|

Micro

|

Sales of goods |

Purchase and then resale of comics, sale of handmadejewellery... |

71% |

€82,200 |

|

Services

|

Passenger transport, rental of a furnished apartment, a car or a Finance Committee, DIY or gardening |

50% |

€32,900 |

|

|

Micro

|

Provision of services |

Home tutoring,

|

34% |

€32,900 |

|

Micro

|

Unfurnished rental |

Rental of a cellar, an attic,

|

30% |

€15,000 |

Source: Senate Finance Committee

Taxpayers coming under the micro-tax system can opt for the micro-entrepreneur system (formerly auto-entrepreneur) , which in particular includes an option for a flat tax in discharge of income tax instead of progressive scale taxation after application of a tax allowance. The micro-enterprise status is discussed in the section of this report devoted to the tax system of online platform users.

Above these thresholds, the taxpayer is compulsorily subject to the ordinary income tax system, which allows the exact amount of all expenses to be deducted this is more complex, but also more suited to professional activities. In addition, if the gross income exceeds the VAT exoneration thresholds, the taxpayer is subject to VAT, that he must declare, collect and pay . However, it should be stated that at these levels of turnover 14 ( * ) , there is no doubt about the professional nature of the activity : in these situations, current tax law poses no particular problem in being applied to the online platform economy and the question of occasional and sideline income, the subject of this report, does not arise.

Taxpayers eligible for the micro-tax system can also opt for the income system , if they believe that this is more advantageous to them. According to some platforms heard by the Working Group, it appears that this is the case in particular for car rentals and, where application of the kilometre scale is preferable, for the calculation of expenses, to a proportional tax-free allowance.

Besides these ordinary law systems, users of online platforms may be taxable in accordance with a series of special, complex systems and probably largely unknown to users seeking only a modest income supplement, unconnected to their main activity: “artistic” and “non-artistic” photographers, capital gains on precious metals, fruit and vegetable sales, car boot sales, etc. The rental sector, in particular, is characterised by a wide diversity of systems :

- the short-term rental of furnished property , which falls under the ordinary law micro-BIC regime, the most common on platforms such as Airbnb ;

- unfurnished property rental , which benefits from the régime micro-foncier , i.e. a proportional tax allowance of 30% within the limit of gross annual income of EUR 15,000. This system mainly concerns platforms for the rental of cellars, garages and storage between private individuals, such as Costockage , Ouistock and Jestocke ;

- professional furnished property rental(LMP) status , which, under certain conditions, allows the person to benefit from the micro-BIC system 15 ( * ) ;

- the system applicable to bed & breakfast ;

- the system applicable to listed monuments, etc.

In conclusion, money received via online platforms is therefore in principle taxable under the conditions of ordinary law, i.e. from the first euro: Contrary to what is sometimes claimed, there is no grey areaas regards income tax, but only a poor application of inappropriate rules .

There are however two particularly significant exceptions for the online platform economy which by their nature are exempt: second-hand sales and cost-sharing. However, the definition of the former is too confusing and that of the latter, too restrictive.

B. THE EXEMPTION OF SECOND-HAND SALES: CLEAR RULES BUT DIFFICULT ENFORCEMENT AND MONITORING

As regards taxation, second-hand sales are exempt from income tax . Under the terms of Article 150 UA of the General Tax Code, gains realised when selling movable goods or rights relating to these goods are exempt provided their sale price is not greater than EUR 5,000 16 ( * ) . Household furnishings, household appliances and cars are exempt regardless of their sale price.

This exemption is implied by Article L. 110-1 of the Commercial Code, which defines, in particular a commercial transaction as any purchase of movable property for resale , either in its original condition or after having transformed and used it : a second-hand sale is therefore where a private individual sells an item of property that he previously acquired or received for his own use, and not for the purpose of reselling it.

The distinction between second-hand and commercial sales is of great importance given the many fake private individualspresent on some online marketplaces , and in particular on those that request little information from their sellers and/or who are not intermediaries in the transaction. In these situations, there are significant losses of tax revenue, not only as regards income tax or corporation tax, but also in relation to VAT 17 ( * ) , as well as manifest distortions of competition.

However, for private individuals acting in good faith, it is not always obvious whether a sale is of a casual or professional nature. Above the EUR 5,000 limit, and whenever the activity is carried on, on a regular basis , the private individual is, indeed, subject to income tax, and must in principle affiliate himself to the self-employed workerssocial security system (RSI) as a trader, and, if applicable, as a micro-entrepreneur. The question of determining the regular nature of the activity arises then with the same complexity as for the other income (see above).

During the Working Groups hearings, the tax authorities argued that the legal position was clear, and that it was unnecessary to change it: whenever a sale is not a second-hand sale, it is taxable . This is a self-evident truth: The question does not concern the principle but the criteria for making the distinction and effective enforcement of these criteria, in a context where it is impossible to monitor whether taxpayers comply with their declarative obligations (see below).

In addition, sales between private individuals on online platforms such as Leboncoin , eBay and Vide-Dressing are subject to the provisions governing jumble and car boot sales , designed at a time when this type of trading was occasional and exclusively physical. Article L. 310-2 of the Commercial Code thus provides that private individuals not registered in the commercial register are allowed to participate in jumble and car boot sales for the exclusive purpose of selling personal and used objects at most twice a year .

Article R. 3219 of the Criminal Code also specifies that the organiser therefore in theory the online platform must keep a register which includes the last name, first names, capacity and address of each participant, as well as the nature, number and date of issue of the identity document produced by the latter with an indication of the authority which issued it and, for non-professional participants, an indication of the deposit of a sworn statement of non-participation in two other events of the same kind during the calendar year.

In its report of May 2016 on collaborative platforms, employment and social protection (see below), the General Inspectorate of Social Affairs (IGAS) rightly considers that this formalism and the limitation to two sales per year no longer seem to match the situation of the practices of the digital society , the use of collaborative platforms now being very widespread by private individuals .

C. THE EXEMPTION OF COST-SHARINGBY THE TAX INSTRUCTION OF 30 AUGUST 2016: A WELCOME BUT TOO NARROW CLARIFICATION

The only significant development as regards the taxation of income derived from online platforms is t he tax instruction of 30 August 2016, which has clarified the definition of cost-sharing for so-called co-consumptionactivities. Long awaited by the platforms, this tax instruction has the merit of bringing together the criteria that can allow an exemption for cost-sharing , criteria that up to then were scattered, confused, and sector-specific rather than fiscal in nature.

|

Non-taxation of income received within the

context

Tax instruction of 30 August 2016 excerpts In accordance with Article 12 of the General Tax Code, income realised by private individuals for their activities of any kind is in principle taxable, including income from services rendered to other individuals when the contact is facilitated in particular by collaborative platforms. However, not taxing income derived from co-consumptionactivities which are cost-sharing is accepted provided that they comply with the following cumulative criteria related to the nature of the activity and to the amount of shared expenses . Where these criteria are not met, the realised income is a profit taxable under the conditions of ordinary law []. 1 st condition: income received for co-consumptionby private individuals The income realised by a private individual for cost-sharing which can benefit from the exemption is that received for co-consumption, i.e. the provision of a service which also benefits the private individual who offers it , and not only the persons with whom the costs are shared. Income received by legal persons or income received by natural persons for their business or directly linked to their work does not fall within the scope of co-consumptionand therefore is not exempted. Income derived by a taxpayer from the rental of an element of his personal assets such as, for example, the rental of his passenger vehicle or rental, seasonal or otherwise, of his main or secondary residence does not benefit from this exemption. 2 nd condition: nature and amount of the expenses The income realised by an individual for cost-sharing which may benefit from the exemption is income, which does not exceed the amount of the direct costs incurred on the occasion of the service which is the subject of the cost-sharing, not including the taxpayers share . This condition relating to the amount received must be assessed strictly: the amount received must cover only the expenses incurred upon providing the service, excluding all costs not directly attributable to the service in question , in particular the costs related to the acquisition, maintenance or the personal use of the propert or tools used for the shared service. In addition, shared expenses must not include the share of the person who offers the service . Indeed, the concepts of cost-sharing and co-consumptionassume that this person personally bears his own share of the expenses and receives no form of direct or indirect remuneration , for the service that he provides and from which he benefits at the same time. In other words, the taxpayer who offers a service for which he shares the expenses is counted as a person in calculating the shared expenses. When the realised income exceeds the amount of the shared costs, it is taxable from the first euro. Source: Bulletin officiel des finances publiques (BOFiP), BOI-IR-BASE-10-10-10-10-20160830 |

Among the activities that can benefit from the exemption, the tax instruction cites three examples: car sharing, sea excursions, and the organisation of shared meals (or co-cooking).

|

Sharing expenses: three examples Car sharing has its own legislative basis: under the terms of Article L. 3132-1 of the Transport Code, car sharing is distinguished from taxi and private hire driver activities in that it consists of the joint use of a motor vehicle by a driver and one or more passengers, carried out on a non-financial basis, except for a sharing of the costs, for a journey that the driver makes for himself . The proposed price must therefore cover only the costs directly incurred because of the shared journey, i.e. the fuel and tolls, but not, for example, a contribution to the car insurance . As a practical rule, the tax instruction specifies that the taxpayer may use the kilometric allowance to assess the total cost of his activity, rules established by Blablacar (see below). With regard to sea excursions , offered for example by sites like Boaterfly , the law states that the requested participation must be only for the costs directly incurred for the excursion, i.e. the costs of fuel, food, mooring and remuneration of the staff on board during the said excursion ” . By analogy, these rules are applied to plane sharingactivities , offered for example by the Wingly platform. They are also set out very clearly on the website page dedicated to the plane sharing etiquette: exceeding the expenses-sharing pro-rata means not only breaching Wingly s code of ethics but above all results in creating a risk. Indeed, any flight not subject to pro-rata cost-sharing then becomes a commercial flight. The pilot is then no longer protected by his insurance in the event of a plane problem. In order to ensure your safety and the long-term continuation of plane sharing, observation of this rule is essential . In its Decision of 22 August 2016 18 ( * ) authorising plane sharing in France, the General Civil Aviation Directorate (DGAC) specifies that pilots are permitted to share their flights with passengers provided they do not make a profit and pay their own share of the flight. Finally, with regard to co-cooking , offered for example by the VizEat website, the exemption applies to a private individual who organises in his home a meal for which he shares only the food and drink costs with the guests and for which he receives no other remuneration. Therefore, for example, requesting participation for the purchase of kitchen equipment is excluded . Similarly, take-away meals prepared by private individuals, as on the Belgian platform MenuNextDoor , are excluded. Source: tax instruction of 30 August 2016 and Finance Committee of the Senate |

Although the clarification made by the tax instruction of 30 August 2016 must be welcomed, its actual effect must not be overestimated which is hardly surprising, with regard to a doctrinal text written without changing the law.

In fact, the definition of cost-sharingremains extremely narrow, and leaves aside a significant part of the collaborative economy, including when users do not make any profit and try simply to reduce their expenses. In particular, it does not cover the rental of housing or movable property for example a car on Ouicar or a drill on Zilok where their owners only try to cover the cost of their purchase. In the course of its lifetime, a drill is on average only used for 12 minutes : sharing such an unused good, although relevant economically and ecologically, is not with regard to taxation considered as cost-sharing : it is taxable from the first euro, and subject to social levies of 15.5% on income from assets.

This is also true for a private individual who hires out his car to cover his expenses (depreciation, insurance etc.), and even though a car is on average used for only 2.7% of the time , and when it is used, three out of four times it is by the driver alone in the vehicle.

Likewise, a private individual preparing meals in his home for other private individuals cannot benefit from the measure if they only collect the meals from his home, without eating them on the spot.

In addition, even for those activities meeting the two conditions needed to qualify for cost-sharing, it is not always easy to define exactly what the participation of each person can or cannot cover .

However, once it involves an activity that is carried out frequently or one that is relatively expensive, such as boat or plane sharing, the amount of money at stake becomes significant, the supporting documents requested are more precise, and the risks of being subject to a tax adjustment increase including when the taxpayer acts in good faith.

In conclusion, it appears therefore that as regards taxation, the choice to preserve the framework of the existing law does not solve the problem posed by the growth of exchanges between private individuals on the Internet . The taxable nature or otherwise of income is determined on a case-by-case analysis, on the basis of complex doctrine and case-law designed for a world of physicaloccasional exchanges. While the digital transformation has greatly increased these exchanges and made most transactions traceable from the first euro, this ambiguity is no longer possible: for the legal certainty of both the users and the platforms, a clear rule, if possible at the legislative level, is necessary .

II. AS REGARDS SOCIAL CONTRIBUTIONS, THE PROBLEM LIES IN THE DISTINCTION BETWEEN PRIVATE INDIVIDUALS AND PROFESSIONALS

As regards social contributions, all income derived from professional activities is subject to social contributions and results in affiliation to a social security regime. However, a professional incomeas applied to income tax does not necessarily match with the definition of professional activityas regards social protection 19 ( * ) .

However, making the distinction between private individuals and professional workers is not easy . Indeed, although with regard to taxation, any income is in principle subject to income tax (see above), this is not the case as regards social contributions. The affiliation to the social security as a self-employed worker entails, for online platform users, significant consequences : the payment of social contributions of course, but also various procedures and obligations, including sector-specific areas.

A. AMONG PLATFORM USERS, MANY PROFESSIONALS ARE UNAWARE OF THEIR STATUS

1. Online platforms professionals: self-employed workers and micro-entrepreneurs

The professional self-employed workers 20 ( * ) of online platforms in principle contribute to the self-employed workerssocial security regime (RSI) , or otherwise the general social security regime 21 ( * ) .

Subject to their annual turnover not exceeding the thresholds of the micro-tax system and VAT exemption (see above), i.e. EUR 82,800 for sales of goods or 33,100 for services 22 ( * ) , these professional users can opt for the micro-entrepreneur system , which simplifies the formalities for founding a company, the payment of social charges and contributions at a flat rate, and optionally the payment of income tax or a fixed rate basis paid at the same time as the social contributions.

The micro-entrepreneur system: summary

|

Activities |

Examples of

|

Social contributions |

|||

|

Alone |

With payment in

|

||||

|

Micro

|

Sales of goods |

Purchase/resale,

|

13.10% |

14.10% |

1% income tax |

|

Services

|

Transport, rentals, DIY or gardening at home, etc. |

22.70% |

24.40% |

1.7% income tax |

|

|

Micro

|

Provision of services |

Creation of a logo, webdesign,

|

22.70% |

24.90% |

2.2% income tax |

|

Liberal profession activities |

Consultant, etc. |

22.50% |

14.10% |

2.2% income tax |

|

Source: URSSAF and Senate Finance Committee

During hearings held by the Working Group in different countries, it became clear that the micro-entrepreneur system was a very clear advantage in France for developing the economy collaborative in its professional part . In particular, this comment was often made during interviews conducted in Belgium (see below).

2. The discouraging complexity of moving from non-professional to professional status low-stake online activities

That said, the micro-entrepreneur system by definition relates to professionals: the issue is therefore knowing when exactly a user of online platforms who considers himself to be a private individual becomes a professional , and must accordingly join a social security system and comply with the declarative obligations and sector-specific rules.

However, currently, there is no criterion that is both simple and objective that can be used to distinguish professionals from non-professionals . Users therefore have no choice but to rely on complex criteria, criteria that are defined case by case and based on complex doctrine and case-law of which escape the vast majority of people.

In principle, any gainful activity carried out on a regular basis 23 ( * ) by a private individual is a professional activity , and results in compulsory affiliation to a social security system. The concept of a regularactivity does not imply any minimum in terms of income received, time spent or frequency of transactions or sales . Few but periodic actions may be a professional activity. Evidence of the activitys professional nature may be provided by any means; it can include the use of a tool of a professional nature, or the organisation of a sales channel. Generally, the doctrine and the Court use the highly subjective concept of the sellers intentionality .

In its report of May 2016 on collaborative platforms, employment and social protection, the General inspectorate of social affairs (IGAS) also emphasises the fact that no condition is linked to the duration of the work : affiliation and social contribution liability in principle apply to a casual job, a helping hand, that of an occasional job or of low importance such as a ”gig job. The sideline nature of an activity, predominant among collaborative workers, has no impact on the remuneration that is subject to social contributions .

It follows, of course, that a self-employed worker registered on a platform like Hopwork or Upwork , or a private hire driver using Uber or LeCab , must be affiliated to social security and pay contributions which is perfectly normal. However, it also follows that a person offering a few hours of DIY or looking after animals via a platform, or selling a few hats knitted at home, must in principle also be affiliated to the RSI (or where appropriate the general regime) in order to do so.

This obligation may apply even when the activity is purely amateur and just a sideline activity without any link to their main activity, and even if it produces only a few tens of euros of income per year or is a loss-making activity.

However, for someone whose activity on an online platform is only a sideline activity, switching from private individualto professionalstatus may well deter them they lose any desire to keep up the activity.

|

Self-employed workersobligations As a self-employed worker, the user of an online platform is subject to ordinary law and must pay social contributions, pay the Corporate land property tax (CFE) contributions to the Chamber of commerce and industry (CCI) or Chamber of Craft Trade (CMA) and the contribution to vocational training. Even more than the compulsory contributions, the administrative constraints, both general and sector-specific , may be the most dissuasive. A natural person carrying out a professional activity must indeed, among other things: - report the existence of their company, complete the incorporation formalities with a business creation centre; - register it in the Companies and Trade Register (RCS) or the Craft Trade directory (RM); - take out professional insurance; - open a bank account dedicated to the activity; - follow a course before establishing the company, which for the creation of a craft activity must be paid for; - obtain a qualification or professional experience for activities such as building, automotive, food, hairdressing and beauty parlors, all activities which, in certain forms, can be found on collaborative platforms; - comply with the obligations laid down by consumer law, health and safety standards, etc. Compliance with these obligations is controlled by the administrative authorities in their different fields : the Labour Inspectorate, the URSSAF 24 ( * ) , the DGCCRF 25 ( * ) etc. Source: Senate Finance Committee |

In any event, the law does not lay down any income threshold above which an activity must be regarded as professional . Certain informalthresholds are sometimes referred to 26 ( * ) , but they are impossible to verify and very fragile at the legal level. In the absence of simple and objective criteria, it is therefore the responsibility of the users of the platforms themselves, under the control of the inspection services and the courts, to determine on a case by case basis whether they actually carry out a professional activity.

However, the consequences are potentially very serious: reclassification as undeclared work would threaten the business model of many platforms, but conversely, the scarcity of controls allows activities to prosper under conditions of unfair competition.

In the physicalworld of jumble sales, car boot sales, amateur DIYers and services between neighbours, these rules were accepted for a simple reason: they were simply not applied, because they were not applicable. But the question becomes critical in the context of the platform economy , where these activities, until recently difficult to identify and control, have become massive, standardised and often traceable to the nearest euro.

However, as the IGAS rightly stresses, these activities generating small amounts of income cannot really develop with the same level of regulatory and social constraints as professional independent activities : the hidden administrative costs related to carrying out a professional activity [] as well as the level of compulsory contributions are significant compared to the income generated occasionally and from sideline activities . In other words, although the current rules do not pose any problem for realself-employed workers carrying out their activity via online platforms, they are at the very least discouraging for private individuals only seeking a modest supplement to their income: applying the rules would result in these new online activities losing their interest entirely , despite being a welcome boostfor many people, especially the long-term unemployed or those on low income, and not applying them leads to a situation of legal uncertainty which is detrimental to everyone . Obviously, it is this second situation which predominates and which needs resolving.

Therefore, the Working Group considers, like the IGAS, that the immediate challenge is to clarify the rules of affiliation to the social security of collaborative workers, taking their income into account under conditions of fair competition in relation to the traditional sectors .

B. TWO THRESHOLDS FOR COMPULSORY AFFILIATION TO SOCIAL SECURITY CREATED IN 2017: A USEFUL YET INCOMPLETE STEP FORWARD

1. Compulsory affiliation when income from rental of movable property exceeds EUR 7,846 and when income from rental of furnished accommodation exceeds EUR 23,000

Article 18 of the Social Security Financing Act for 2017 27 ( * ) provided an initial response to this problem, by establishing two thresholds for compulsory affiliation to the social security , respectively for the rental of furnished accommodation for short periods and for the rental of movable property (cars, tools, etc.).

Since 1 January 2017, in principle, natural persons whose gross annual income exceeds the following thresholds are therefore compulsorily affiliated to the social security regime of self-employed workers (RSI), or if they so choose to the general system :

- EUR 23,000 for the rental of short-term furnished accommodation , or more precisely direct or indirect rental of furnished residential premises, [] when these premises are rented to customers staying on a daily, weekly or monthly basis and not residing there .Therefore rentals of accommodation by private individuals on platforms such as Airbnb or Abritel are covered by this measure. The EUR 23,000 threshold already exists for professional furnished accommodation provider (LMP) , whose other conditions are however more restrictive (see above): in practice, the LMPsystem has therefore been expanded in relation to social contributions, but remains unchanged in relation to income tax;

- EUR 7,846 (in 2017) for the rental of movable property . The criterion laid down by the Act being that of proceeds greater than 20% of the annual “ plafond annuel de la Sécurité sociale ( PASS )”. This activity 28 ( * ) is mainly aimed at car rental (for example via Drivy or Ouicar ), but also applies to any other type of object, from prams to boats, taking in barbecues and cameras on the way (for example on Zilok ).

When his income exceeds these thresholds, the person is subject to social security contributions on all his income, i.e. from the first euro.

Below these thresholds, the income is not considered to be income from a professional activity, but personal immovable or movable property income . It is therefore, in principle, subject to income tax and social levies of 15.5% on property income.

These thresholds apply to all activities and are not specific to the activities carried out via online platforms. They are “ceilings thresholds” beyond which affiliation is mandatory, but do not prevent affiliation at a lower level of annual proceeds.

2. A useful yet incomplete clarification, which does not cover sales or services

It is a useful clarification . Indeed, although it is important to allow the sharing economy to its “life”and not to hamper it with restrictive rules from the first euro earned from a sideline activity, it is not acceptable that it can become a real shadow economy, with fake private individuals entering into direct competition with professionals who do not pay social contributionsand ultimately not benefiting from any social protection either. In this regard, the establishment of a threshold that clearly distinguishes income derived from the private ownership of property from that from professional rental is a step in the right direction .

In particular, two changes that came about in the course of the parliamentary debates should be welcomed 29 ( * ) :

- the increase from 10% to 20% of the PASS for the threshold applicable to rentals of movable property : the level of EUR 3,923 gross per year originally proposed by the Government, i.e. EUR 327 per month, may appear to be very low, especially since it only applies to gross proceeds, which in no way implies that the private individual makes a significant net profit or even any profit at all. As Francis Delattre, the Finance Committee's rapporteur opinion 30 ( * ) , an individual who occasionally rents his car, his motor home, his lawnmower or his drill, would have been considered to be a self-employed worker, and would have had to join the RSI, with all the constraints and obligations that this entails. Is this really what millions of French citizens engaged in the sharing economy want, and who often only derive sideline income from it? ;

- the possibility to opt for an affiliation to the general regime , which, in particular, allows people who are already employees not to have to join two different systems 31 ( * ) .

However, the rules laid down by the Social Security Financing Act for 2017 only settle a small part of the problem. The Secretary of State responsible for the budget, Christian Eckert, acknowledged this problem during the debates in the National Assembly: let us be clear on this: this article does not claim to solve everything .

First and foremost, this clarificationis limited to the case of rentals of furnished accommodation and movable property, but sets no minimum threshold for services on the one hand, and for sales of goods on the other hand, leaving out a considerable proportion of the collaborative economy . Like those of the General directorate of public finance (DGFiP), the representatives of the Social security directorate (DSS) heard by the Working Group took the view that the existing law posed no problem, and that there was no reason to change it: a sale or provision of a service are a professional activity from the first euro of profit.

It follows that a student offering some mathematics tuition or one evening of babysitting per week via an online platform should in principle join the RSI as soon as he receives his first euro . The same is true for a pottery enthusiast who occasionally sells his own products in a Sunday market. However, although there is no doubt about the principle of affiliating to the social security when the activity is professional, one can nevertheless doubt the social acceptability of affiliation from the first euro for occasional or sideline activities , sometimes carried out as a hobby or by a simple enthusiast.

Moreover, it could well prove to be hard to distinguish those activities covered by the thresholds (rental of movable or immovable property) from those activities not targeted (sales and services). Thus, must the services linked to the rental of an apartment on Airbnb , not only handling-over the keys and the cleaning but also the advice given to tourists about the neighbourhood, be taken into account in calculating the thresholds? A series of unjustified and contentious affiliations can legitimately be feared, or on the contrary a multiplication of deadweight effects.

In addition, affiliation to the social security for the activities carried out via platforms and whose professional nature is not clear is problematic in several cases and in particular:

- for people already affiliated to social security for another activity , whether they are employed or self-employed. Indeed, and unlike taxation, social contributions are defined by the existence of rights in return (sickness insurance, retirement pension, etc.): therefore, these people would have to pay additional contributions, without benefiting from a higher level of protection, which could be hard to understand. People with several different jobs or people who work and receive a retirement pension at the same time who pay solidarity retirement contributions, could find themselves in this case;

- for civil servants , who are required to get written authorisation for having a second activity from their superior, limited in time 32 ( * ) : strict application of the law would make it illegal for any civil servant to be active on a services or sale platform if they receive more than EUR 7,846 per year from a property rental platform or more than EUR 23,000 per year from an accommodation rental platform. The same problem arises for professions subject to a strict ban on undertaking any form of commercial activity , such as judges, police officers and certain regulated professions;

- for the unemployed and the recipients of minimum social benefits (disability pension, RSA, AAH, etc.), who could lose part of their rights by renting their apartment or their car or by offering some DIY services in their neighbourhood, even though this may be essential extra incomefor them.

Moreover, this socialclarification does not seem consistent with the taxclarification of the definition of co-consumptionactivities if they are by nature exempt as regards to tax, what is the justification that simply crossing gross proceed thresholds necessarily results in affiliation to the RSI, even when this is also co-consumption?

C. CORPORATE LAND PROPERTY TAX, A TAX THAT APPLIES TO ALL PROFESSIONAL WORKERS

According to the hearings organised by the Working Group, the greatest astonishmentof online platform users redefined as self-employed workers relates to the enterprises corporate land contribution ( cotisation foncière des entreprises , CFE) .

Under the terms of Article 1447 of the General Tax Code, the CFE is due each year by businesses natural persons or legal entities, companies without a legal personality or trustees who carry out a self-employed professional activity .

The CFE is therefore due, regardless of the legal status of the person liable (company, foundation, micro-entrepreneur, etc.) and the nature of his activity , including if he carries it out as a secondary activity and via an online platform.

Taxpayers, if they do not have professional premises, are thus liable to pay the CFE on the base of their personal residence . In accordance with Article 1647 of the General Tax Code, they are subject to a minimum contribution if their turnover is less than or equal to EUR 10,000. The minimum basis of the CFE is between EUR 214 and EUR 510, depending on the levels voted by the local authorities in the commune in which they are based, which is equivalent to a minimum contribution of EUR 55 to EUR 132 33 ( * ) .

However, as for income tax and social security contributions, the concept of a activity does not meet any clear and objective criteria , but depends on complex case-law and doctrine and differs from the one which applies to income tax. The Bulletin Officiel des Finances Publiques 34 ( * ) (BOFiP) specifies only that this condition is deemed to be satisfied when the actions which characterise the activity are carried out repetitively ” .

The situation is further complicated by multiple exemptions from the CFE , which result from a vision of the economy that is out of phase with that of the digital platforms, but which may be applied. For example:

- the exemption of independent craft workers : 1° of Article 1452 of the General Tax Code provides that workers who work either as contractors for private individuals, either for themselves and with materials belonging to them, whether or not they have premises or a shop, when they use only the assistance of one or more apprentices aged twenty years or under at the start of the apprenticeship and who have an apprenticeship contract are exempt;

- the exemption of some teachers , 3° of Article 1460 of the General Tax Code distinguishing for example mathematics courses from kitchen or sewing courses.

D. SOCIAL LEVIES, THE FORGOTTEN PART OF THE DEBATE?

The social levies include the five following elements : the “ Contribution sociale généralisée ” (CSG), the “ Contribution pour le remboursement de la dette sociale ” (CRDS), the “ prélèvement social ”, the “ contribution additionnelle ” and the “ prélèvement de solidarité ”.

Unlike social contributions, due by professional affiliated to a Social security regime (see above), social levies are considered universal taxes, which do not give an entitlement to any specific social benefit 35 ( * ) .

Even when they are not considered to be self-employed workers and affiliated as such to the Social security, and even when they are not liable to pay income tax , users of online platforms are as any taxpayer subject to social levies on their income, at the rate of:

- 8% on income from activities : DIY, babysitting, cooking, etc.

- 15.5% on income from assets : this means that a private individual who occasionally rents his drill or his bike without exceeding the EUR 7,846 threshold could in principle be liable to pay social levies on these elements of his assets, from the first euro. Beyond EUR 7,846, he is regarded as a self-employed worker, and therefore affiliated as such to the Social security and liable to pay social contributions on income from activities.

III. REPORTING, CONTROL AND COLLECTION:

A. SELF-REGULATION: AN ENCOURAGING YET INHERENTLY LIMITED RESPONSE

1. An effort by the platforms to identify professional users

Due to their sector of activity, some online platforms are, by definition, reserved only for professional sellers or service providers . This is the case for example of some 22,000 private hire drivers and licensed passenger transport drivers, or the 42,000 qualified self-employed workers registered on Hopwork . All have a professional status (micro-entrepreneur, “ Entreprise Unipersonnelle à Responsabilité Limitée ” (EURL), “ Société par Actions Simplifiée Unipersonnelle ” (SASU) etc.), whose supporting official documents are requested by the platform.

Many platforms, however, attract both private individuals and professionals and many users situated somewhere in between the two , without it necessarily meaning that a professionalaccount on a platform implies a legal status of self-employed worker, or the reporting and payment of taxes. Similarly, asking a seller to provide his VAT or company registration number (SIRET) does not guarantee that he will actually declare it.

Of course, it must be recalled here that it is not, legally speaking, the platforms' responsibility to ultimately ensure compliance by the users with their tax obligations .

In most cases, the status of professionalremains a simple declaration . Most platforms simply do not have the human or material resources to make the necessary checks. With regard to the detection of fake private individuals, the CEO of a small platform heard by the Working Group summarised the situation like this: we often observe, we sometimes alert, but we do not remove them from the platform.

That said, identifying the vendors or providers of professional services is most often in the interest of the platforms themselves : professional accounts are often a paid-for service associated with visibility options they are even together with advertising, the base of the business model of those websites that do not take a fee on transactions. There is also an important issue of reputation for example, on Leboncoin , which is the leading real estate website in France, a seller pretending to be a private individual who later on informs the buyer that he must pay agency fees is very bad publicity for the site. Therefore, the priority of these websites is not so much the fight against tax fraud as rooting out scams targeted at users , and in this regard, the professionallabel is a significant guarantee for an economic model which above all is based on trust.

In terms of detecting fake private individuals , the measures taken by the platforms can be broken down into three unevenly implemented stages.

The first stage is to inform users of their tax and social obligations (and also where appropriate obligations specific to their sector), which most platforms have done for a long time in dedicated sections. The two examples below are taken from the sections of two platforms, A Little Market and Zilok , offering respectively "hand-made" objects and objects for rent, and therefore at the heart of the problem of distinguishing private individuals from professionals.

The second stage consists of identifying the professionals and the "fake private individuals" . For this purpose, most platforms have criteria, in most cases confidential and adopted to their economic model, used to identify these users: income or frequency thresholds of transactions, type of products or services offered, scores given by customers etc. On the main platforms, a team of moderators is entrusted with this task. Where applicable, reports by third parties (customers, competitors, etc.) are added to these.

|

Information sections: two examples |

|

|

A Little Market Although selling on the Internet as a private individual or a professional is allowed, each seller is under the obligation to report his sales to the tax authorities . As a private individual , you must report your earnings from your sales on your income tax return in the supplementary form 2042 C in the BIC non professionalcategory. If you wish to obtain more information or help to complete your income tax return (), call 08 or visit the General directorate of public finances website. As a professional , you simply need to report your sales when filling in your income tax return as for the rest of your commercial activity. If you are unsure of something or have a question, we advise you to contact your income tax office directly or the chamber of commerce in your region, or the Union des Auto-Entrepreneurs (auto-entrepreneurs association) if this is the status that you have chosen. |

Zilok The question is not whether you must report your income but how to report your Zilok income in France in your annual income tax return. As a private individual, for the annual income tax return, we declare all our income. Zilok income is not an exemption to this logic, so you are also required to report all your Zilok income to the tax authorities. The tax authorities consider that movable property rentals are non-intellectual service. The movable property rental activity is covered by the BIC, Industrial and Commercial Profitstax system. |