SESSION 3

INTERPARLIAMENTARY COOPERATION

AT

UNION LEVEL

I. INTRODUCTION

Mr Didier Marie, Deputy Chair of the

European affairs Committee of the French Senate

In a few days' time, France will hold the Presidency of the Council of the European Union, and the French Parliament will be organising or co-organising nine interparliamentary meetings. For its part, the European Parliament has already planned to organise 7 additional meetings over the same period, while the current Slovenian Presidency will be adding two more. Most of these 18 meetings did not exist during the last French Presidency, in 2008, which shows the recent increase in interparliamentary cooperation.

But does this increase in the number of meetings go hand in hand with a deepening of the work of these conferences?

I regularly attend Cosac meetings and I hear from colleagues who attend other conferences: we don't always feel that these meetings allow us to really exercise democratic control over the European institutions. The pandemic has also removed one of the benefits of these meetings, which was to create and nurture personal links between parliamentarians from all over the Union, in order to exchange ideas that go well beyond the conference itself.

There have been several recent developments in interparliamentary cooperation, starting with the specialisation of conferences. I am thinking in particular of meetings dedicated to the control of Europol, the control of Eurojust and perhaps tomorrow the control of Frontex. These agencies have the distinctive feature of being European authorities, while bringing together national authorities. Interparliamentary scrutiny is therefore a natural solution.

The Conference on Stability, Economic Coordination and Governance is particularly important because it concerns areas where national parliaments traditionally have a great deal of power: the budget and economic policy. It is particularly important for the countries in the euro zone, insofar as the abandonment of national currencies constitutes an implicit sharing of sovereignty, with the creation of a European Central Bank, which is federal in essence. This far-reaching monetary integration strengthens the unity of the internal market and calls for more integrated economic governance, which must be accompanied by greater democratic control.

This third session will therefore be an opportunity to examine all these aspects and to consider ways of making cooperation between the parliaments of the European Union more effective.

II. INTERPARLIAMENTARY COOPERATION

AT THE POLITICAL AND ADMINISTRATIVE LEVELS, IN THE EURO-NATIONAL

PARLIAMENTARY SYSTEM

Mr Nicola Lupo, Professor of Public Law, Luiss

Guido Carli University, Rome

1. Introduction

First, let me thank the French Senate and, more precisely, Presidents Larcher and Rapin and Doctor Revellat for their very kind invitation to this extremely well-designed symposium, taking place at such a prestigious institution and in the wake of the start of the semester under the French presidency. My contribution will focus on interparliamentary cooperation, at both the political and administrative levels, seeking to demonstrate its crucial, although under-developed, role in the Euro-national parliamentary system.

This contribution does not propose to catalogue all the instruments of interparliamentary cooperation within the European Union, starting from the interparliamentary conferences, because several of the members of the French Senate are much more familiar than me with many of these instruments434(*). Interested citizens should also be able to obtain sufficient information regarding these instruments thanks to the new IPEX website. While the new version of the website represents a clear improvement by comparison with the previous one, it remains aimed primarily at the experts and actors of the process, rather than being for the general public. Perhaps another, separate instrument might be devised, which instead targets the public.

The newest and probably most innovative instrument of interparliamentary cooperation is the Conference on the Future of Europe (COFE), which is experiencing a wide array of mechanisms of participatory democracy435(*). However, it appears too early to assess whether, and if so how, this Conference has succeeded in hopefully designing a new phase of the European integration process.

I prefer to devote specific attention to the institutional context, and its possible interpretation, in which interparliamentary cooperation in the EU develops, framing it in the context of the Euro-national parliamentary system (see infra, par. 2) and highlighting the specificities of interparliamentary cooperation in the EU: in particular, the fact that the constant dialogue between national legislatures and the European Parliament represents a constitutionally relevant dimension within the overall architecture of the European Union. My contribution then deals with two more specific issues, linked to more general trends that are currently of interest to the EU institutions, seeking to analyze, although always in general terms, their effect on interparliamentary cooperation both at a political and at an administrative level: 1) the effects of the Covid-19 pandemic and of the possibility of having some “remote” interparliamentary activity; and 2) the consequences of a more asymmetrical Europe and of bilateral agreements between Member States.

2. The concept of the Euro-national parliamentary system

Many alternative opinions have been advanced in attempts to define the role of parliaments within the EU. The co-existence of multiple levels of political representation is not very common, considering that the EU is not a Federation and that the supranational level is in addition to the traditionally deeply entrenched national mechanism of political representation and, in several Member States, also to the pre-existing elected assemblies at the subnational level436(*).

One of the most commonly used concepts for the purpose of identifying such an environment is that of a “multi-level parliamentary field”. This notion encompasses “a wide range of parliamentary institutions at different levels within the EU” and demonstrates the existence of “a transnational sphere of democratic representation integrated around a set of norms that delineate certain basic values and a shared democratic practice” 437(*).

By comparison with this concept, the reference to a Euro-national parliamentary system aims to highlight that individual parliaments are not alone in playing a game, which is reserved exclusively to parliaments, having at its core the political representation of the citizens. Rather, parliaments, even in their inter-parliamentary relations, are playing the same game as the Executives, consisting of determining the general political direction of the European Union438(*).

That is why the context in which parliaments operate cannot be characterized as just a “field” - i.e., a place where the relations of power may be determined by “less formal resources, such as access to information, seniority, contacts”439(*). Rather, it is a “system”, characterized by legally binding and constitutionally relevant procedures, as well as the confidence relationships that link the national parliaments (or at least their lower Chamber) to their Executives, and the confidence-like relationship between the Commission and the European Parliament440(*).

It is necessary to bear in mind that a confidence relationship between the Government and at least one branch of Parliament is required in 26 of the 27 Member States of the Union.441(*) The only exception is Cyprus, a country which has adopted a classically presidential form of government, based on the strict separation between the President, directly elected by the electoral body, and Parliament.

If we add that all six of the founding Member States were characterized, at the time of the foundations of the European communities, by a parliamentary form of government, it is possible to deduce that the confidence relationship between the Government and the Parliament seems to be a sort of “constitutional tradition” within the European Union. And that the entire institutional architecture provided for by the Treaties, as well as the models for the implementation of EU law presuppose, for their orderly functioning, the existence of a confidence relationship between Parliament and the Government within the Member States, in order to completely, although indirectly, ensure the legitimacy and the accountability provided by Article 10 TEU.442(*) France is, of course, an exception in this respect, and a very relevant one: as the 2005 referendum on the Constitutional Treaty showed very clearly, whenever the will of a national government and the orientation of its public opinion do not coincide, problems arise not only for that country but for the European Union too.

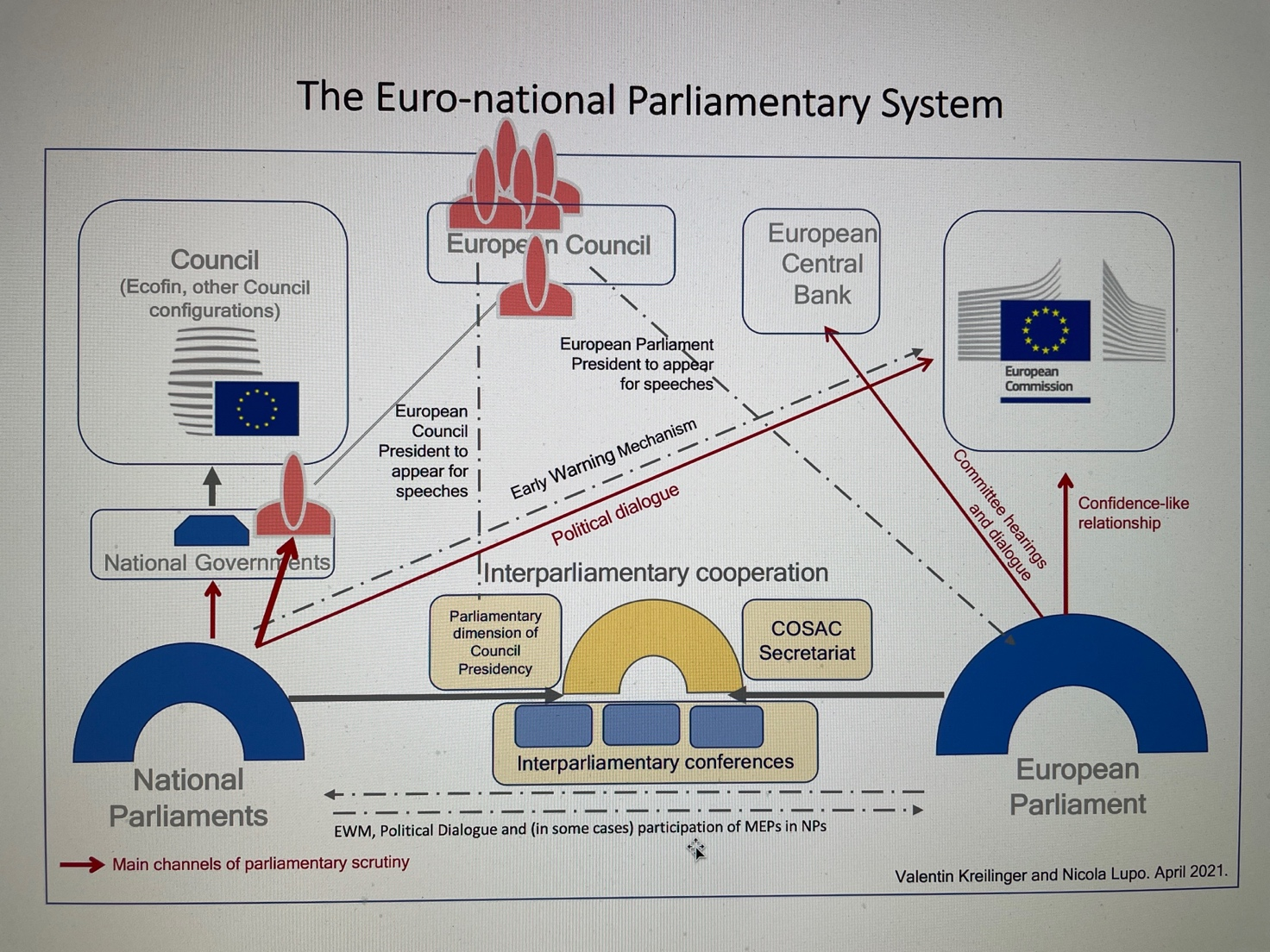

Anyway, a graphic (simplified) representation of the Euro-national Parliamentary system follows:

You might place yourself in either of the national institutions featured in the graphic (either national parliament or national government) and see how many relationships your institution is called upon to develop together with national as well as with the European Union's institutions. Or, of course, vice versa, adopt the viewpoint of a European Union's institution. Or even imagine yourself as one of the bodies of interparliamentary cooperation. All these relationships structure the Euro-national parliamentary system, often giving rise to Euro-national procedures which encompass both European and national institutions and are regulated by both EU and national law.

3. The functions of interparliamentary cooperation in the European Union

The concept of the Euro-national parliamentary system helps us to identify the main functions of interparliamentary cooperation in the European Union. To explain its contribution to the overall EU architecture, it might be useful to address some of the myths concerning this dimension, thereby clarifying what interparliamentary cooperation is not, in light of how the system is designed.

First, as is clearly visible from the graphic and as might also be inferred from the text of the Treaties, interparliamentary cooperation does not operate as an additional “virtual” Chamber nor does it create a further and autonomous channel of representation or legitimacy within the European Union. The channels of representation are dual and are necessarily coexisting, according to Art. 10 TEU, arising in the context of the European Parliament on the one hand, and of National Parliaments (and national citizens) on the other.

Second, and at the opposite end of the spectrum, interparliamentary cooperation is not merely an arena reserved exclusively for parliaments, aimed at ensuring a mutual exchange of information and best practices. Of course, these functions can also be served by interparliamentary cooperation, but in the European Union the stakes are necessarily much higher: in this context, interparliamentary cooperation is a tool which is instrumental to policy-making, called upon to strengthen democratic accountability, as well as to influence the crucial confidence relationships existing at the national level and the definition of the general political direction of the European Union.

In more positive terms, this means that interparliamentary cooperation is an essential element that structures the Euro-national parliamentary system and, if appropriately developed, could contribute to increasing the accountability of the (fragmented and therefore powerful) Executives within the European Union.

This function of interparliamentary cooperation has become even more necessary in light of the evolution of the European Union. When the Community method was the only option, there was arguably no specific collective role for national parliaments within the European Communities. Each of them was just called upon to appoint its representatives in the European Parliament and also to scrutinize the activity of its Executive with respect to its European policy. During this era, which, as is well known, ended with the Maastricht Treaty, national parliaments were often hidden behind their Governments, and the general political direction was primarily determined by the European Commission, which represented the main engine of the integration process, whose political accountability was at least partially ensured by the European Parliament.

After the Maastricht Treaty, once the intergovernmental dimension of the European Union had first been created and then further developed in the following years, a clear gap emerged in parliamentary accountability. To put it simply, also relying upon our graphic, having regard to the activity of the European Council as well of other intergovernmental bodies, there is almost no form of effective scrutiny exercised by the European Parliament. At the same time, each national parliament is able, at best, to scrutinize the activity of its own Executive, verifying how it managed to pursue and protect the national interests443(*). Therefore, there is no mechanism to verify whether, and if so how, the European Council and the other intergovernmental bodies are able to pursue and protect the European interests.

The only institutional mechanisms that, in the current institutional picture, are capable of potentially ensuring this kind of collective accountability of intergovernmental bodies are interparliamentary cooperation, and especially the interparliamentary conferences.

So, in our graphic, we might replace the European Council with other inter-governmental bodies, each with its own distinctive features, and with its own corresponding interparliamentary instrument. For example, the High Representative of the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy, facing the Inter-Parliamentary Conference for the Common Foreign and Security Policy and the Common Security and Defence Policy. Or the Ecofin or even more so, given its informal character444(*), the Eurogroup, in correspondence with the Interparliamentary Conference on The Inter-Parliamentary Conference on Stability, Economic Coordination and Governance in the EU (the so-called Art. 13 Conference, in relation to which Diane Fromage is going to focus her contribution). Or even EUROPOL, together with the Joint Parliamentary Scrutiny Group on EUROPOL.

Of course, one might argue that all the existing instruments of interparliamentary cooperation are insufficient and propose that new bodies be established. The most renowned proposal in this respect is that advanced by Stéphanie Hennette, Thomas Piketty, Guillaume Sacriste, and Antoine Vauchez, which suggested the establishment of a new assembly for the Eurozone, comprising four fifths national members of Parliament (MPs) delegated by national parliaments from the Eurozone and one fifth members of the European Parliament (MEPs)445(*).

4. The differences between interparliamentary cooperation in the EU and parliamentary diplomacy

It is important to emphasize and to clarify the context in which EU interparliamentary cooperation is taking place in order to demonstrate that its nature and function are almost completely different from other forms of interparliamentary cooperation: in the European Union the aim pursued by interparliamentary cooperation is rather distant from so-called “parliamentary diplomacy”446(*). In this case, as already remarked, parliaments are debating matters relating to the political direction (“indirizzo politico”) and oversight and are doing the job for which they were conceived: holding the Executive to account and contributing, although indirectly, to the approval of EU legislation447(*).

Notwithstanding this, the instruments used in relation to interparliamentary cooperation in the EU are often the same as those applied to parliamentary diplomacy, although for the purpose of achieving different outcomes. This might generate some confusion, and may also provide some rather easy arguments to those who seek to avoid parliaments' full development of these functions.

Indeed, many barriers tend to be raised to prevent the full employment of the instruments of interparliamentary cooperation. Of course, this is done first of all by the Executives; sometimes by the European Parliament, which aims to avoid the creation of new bodies it cannot fully control; and in some cases, even by some national Parliaments, which prefer to leave a greater margin of action to the national Governments and to the European Commission in framing EU policies. All these protagonists of the Euro-national parliamentary system thus prefer to assign a very limited role to interparliamentary cooperation and can easily adopt arguments, both explicit and implicit, based on the fact that the main instruments used appear to be extremely similar to those that the same MPs also encounter in their relations with extra-EU institutions.

This ambiguity helps to explain most of the debates regarding the main features and limits of the interparliamentary conferences. Their establishment as bloated, plethoric bodies, strictly organized according to nationality, and even allowing for a variable composition of national delegations, did not encourage their intensive use as institutions contributing to ensuring the political accountability of the Executives within the EU.

Further elements of weakness arise in relation to the frequency of their meetings, which are held only twice a year, based on a rather ritualistic and inflexible schedule, and to the adoption of very broad and discontinuous agendas and to the lack of continuity in MPs' membership and participation. These arrangements, which were borrowed from the traditional procedures for the meetings of parliamentary diplomacy, do not enable the interparliamentary conferences to adapt their activity to the various stages and contents of the inter-governmental decision-making process in the EU, or to structurally incorporate them into the workings of domestic parliaments448(*). Finally, discontinuity in the presidency and the dependent arrangements of the secretariat, which also derive from the traditional habits of parliamentary diplomacy, represent further weaknesses of the interparliamentary conferences.

5. The debate on the administrative dimension of interparliamentary cooperation

The highlighted peculiarity of the EU experience applies to both the political and administrative dimensions of interparliamentary cooperation. As is well known, some aspects of parliamentary diplomacy also concern parliamentary administrations: that is, the unelected officials who work for and on behalf of elected representatives, providing support services to the institution of parliament449(*).

Given the complexity and the novelty of the instruments of interparliamentary cooperation in the EU, some scholars have depicted them as originating a kind of bureaucratization process, instead of a real democratization, as the latter would require greater involvement of national parliaments in EU decision-making450(*).

Two counter-arguments might be raised in response to this argument, which is rather smart and solid. First, this enlargement of the role exercised by parliamentary administrations might have happened at an initial stage, soon after the entry into force of the Treaty of Lisbon, with respect to some instruments of interparliamentary cooperation and some new mechanisms aimed at involving NPs in the EU decision-making processes, such as the Early Warning Mechanism451(*). That is, when these instruments were designed and first implemented, more leeway was left to parliamentary administrations, as national MPs clearly needed a stronger degree of assistance from their non-elected staff to navigate these complex processes.

Second, the more significant role assigned to parliamentary administrations on European affairs, compared to the role that parliamentary administrations ordinarily exercise on national policies, may be deemed, at least in part, to represent an effect of a relevant difference between the features of European and national policymaking, regarding the blend between politics and expertise-technocracy. In other words, the crucial role typically assigned to expertise-technocracy in the European Union institutional dynamic requires some adaptations in several member States, in which experts and the non-elected usually play a minor role. This difference may be considered, for example, as one of the reasons underpinning the formation of technocratic governments in Italy452(*).

Noting that this rationale might explain the more extensive role assigned to parliamentary administrations in the development of inter-parliamentary cooperation, it is also possible to point out some options that could help to re-balance the blend between politics and expertise-technocracy in interparliamentary cooperation.

First, assigning a clearer coordinating role to the Speakers' Conference of the multiple mechanisms of interparliamentary cooperation, as imagined by some453(*), might represent a more appropriate level of political decision. This is due to the fact that, normally, the Speakers are prominent political figures, while concurrently bearing the responsibility for their parliamentary administrations. Along these lines, a stronger COSAC (Conference of Parliamentary Committees for Union Affairs of Parliaments of the European Union) should be closely linked to the Speakers' Conference and to the different standing committees (as well as their staff).

A second means of finding a better balance between politics and expertise-technocracy should involve the further development of interparliamentary cooperation through more “interparliamentarism by committee”454(*). Instead of further multiplication of assemblies or conferences, it would be more useful for interparliamentary cooperation to work with greater continuity in smaller groups, in which it is easier for the technical dimension to be given further consideration, especially in the preparatory stages. Moreover, even the establishment of some more document-based exchanges between parliaments should encourage this kind of evolution455(*).

6. The effects of Covid-19 and of the possibility of having some “remote” parliamentary activity

Before 2020 it was commonly remarked that, over the last decade, the European Union had faced a series of crises which had given rise to important systemic reactions at the supranational level and also, in the institutional balance, a further increase in the role of the Executive456(*).

Of course, the pandemic has further accentuated this trend, in ways that have only partially been assessed, in any case making it even more pressing that the mechanisms of parliamentary accountability operate smoothly, in order to scrutinize the increased activity and powers of the executive. In this context, in might make sense to devote some research, in the future months, to the effects which Covid-19, and the consequent spread of digitalization in parliamentary activity, has had on interparliamentary cooperation.

Obviously, it is too soon to draw any conclusion on this matter. My hypothesis, however, is that the development of digitalization has primarily given rise to negative effects on interparliamentary cooperation at the political level. The periodic meetings of MPs have lost their sense of community and of a common experience that the physical meetings generally brought with them. Of course, the use of digital tools allows the participating MPs to preserve more time, and in some ways increases the number and even the quality of potential participants in these events.

On the contrary, digitalization has had more positive effects for interparliamentary cooperation at the administrative level, simplifying the interchange and increasing the frequency of meetings and dialogue between administrators working on the same dossier.

However, as already remarked, parliamentary administrations should not be seen as an autonomous channel of interaction among parliaments. Rather, they must be used primarily to better structure and support the instruments of (political) interparliamentary cooperation. Parliamentary administrations, by contrast with other bureaucracies, are not entitled to autonomous function, but are uniquely aimed at supporting the activity of MPs: this means that the actual content of their activities may vary significantly and is always determined by the leeway that is left to them by MPs. This room to manoeuvre naturally tends to expand whenever, as in interparliamentary cooperation, MPs need to operate within a complex and multilingual environment.

From this perspective, if appropriately used, and if it encompasses both the political and the administrative levels, the increased digitalization of interparliamentary cooperation might encourage committee activity and assist the preparatory work conducted within parliamentary administrations and also within each political party. As always, the activity of parliamentary committees represents a good way of striking a natural and sometimes even an optimal balance between politics and expertise-technocracy. Indeed, it may also be conducted according to new formats, thanks to the possibility of using digital technologies, with which all MPs are gradually becoming more familiar.

7. The effects of bilateral agreements between Member States and of a more asymmetrical Europe

It is well known that asymmetries between the Member States of the European Union have increased over the last two decades and, according to many, will further increase in the near future, if differentiated integration becomes one of the outcomes of the ongoing reform process, possibly even without the need for amendments of the treaties457(*).

In parallel, a number of bilateral treaties have more recently been signed: the examples of the “Aachen treaty” (also called “traité d'Aix-la-Chapelle”, in French), signed on January 2019 between Germany and France, and of the “Quirinale treaty”, signed on November 2019 between France and Italy, do not need to be analyzed here in detail.

What can be noted is that these bilateral treaties contain some clauses, such as the ones ensuring the mutual participation of members of the Governments in the national Council of Ministers, once per trimester, which seem to have a mainly symbolic, although important, meaning458(*).

These clauses are mirrored by the connected protocols of interparliamentary cooperation, which consequently aim to strengthen the bilateral interparliamentary cooperation, both at the political level and at the administrative level. In one case, a new (bilateral) Parliamentary Assembly has even been established, composed of 50+50 MPs, which meets twice a year, aimed at bringing their working methods closer and ensuring convergent positions within the European Union459(*). Another example aims to strengthen the cooperation between parliamentary committees and to offer staff study visits and periodical meetings aimed at better coordinating the technical activity460(*).

The message to be conveyed through all these clauses, and the regular bilateral relationships that they anticipate, is that the number of relevant cleavages and possible alliances within the European Union is increasing and that, most of all, there is a continuous activity of “co-governing” or “governing together”, which also has an important influence on the daily workings of the respective governments and parliaments. Such activity can, in certain instances, even overcome the traditional principles of national sovereignty according to which no member of a foreign government or of a foreign parliament may take part in the operation of national institutions.

In the European integration, symbols matter, provided that they are the right ones. In several cases of interparliamentary cooperation as well as in some moments of European integration, European Union institutions remain tied to some symbols of traditional international diplomacy, without considering that these represent ordinary ways in which the European democracy functions. Just to quote one example, one might legitimately wonder whether it still makes sense to take group pictures with national flags in the background at every meeting of the European Council or in every interparliamentary conference, as, while these used to be exceptional diplomatic events, they have become rather frequent occasions of “governing together” in the European Union.

With respect to the effects of a more asymmetrical Europe, it is clear that interparliamentary cooperation may represent a suitable response to the asymmetries among Member States, which have increased in number within the EU in recent decades461(*), provided that its instruments are taken seriously and can adapt their formats accordingly462(*). The European Parliament's composition and rights to vote, which differ from those of the Council463(*), cannot be adapted to the different formats of enhanced cooperation and differentiated integration without the Parliament losing its identity as a “proper” parliamentary assembly.

In a more asymmetrical European Union, if interparliamentary cooperation is ineffective in increasing accountability within the EU, the only option to avoid a loss of democracy would be to establish new parliamentary assemblies: in theory, one for each format of enhanced cooperation or differentiated integration, or at least for the most important ones. This is the kind of thinking underpinning the previously mentioned proposal to establish a new assembly for the Eurozone. While this proposal is based on a very effective analysis of the many flaws of democratic accountability and parliamentary scrutiny in the Eurozone, it actually seems to complicate an already complex institutional setting464(*). This is particularly the case when one considers that much can be done, as will be highlighted in the conclusion, through taking seriously and further developing the many instruments of interparliamentary cooperation465(*).

8. Conclusion

Overall, instruments of interparliamentary cooperation represent important opportunities for parliamentary and open deliberation on crucial topics. They must be taken seriously as they contribute to fostering participation in determining the political direction of the EU and to strengthening the circuits of democratic accountability. This is also the reason why it is essential to include and to give voice, within the instruments of interparliamentary cooperation, to national oppositions, that would otherwise not be included in the decision-making process466(*).

The need to include national oppositions raises a kind of dilemma, as the composition of interparliamentary conferences and, more generally, of all meetings taking place within the sphere of interparliamentary cooperation cannot be too restricted. At the same time, it is clear that the existence of plethoric bodies and meetings risk endangering their capacity to accomplish their functions, and their operation is expensive. In this respect, indeed, the increased digitalization might help, as it dramatically reduces operating costs and allows, under certain conditions, the organization of successful meetings with a high number of participants467(*). However, interparliamentary cooperation should not be limited to virtual processes only, since this would alter the distinctive nature of this dimension and endanger its constitutional relevance.

After the approval of the Next Generation EU and in the wake of the reform of the Stability and Growth Pact, it is hard to deny that the European Union needs very well designed and properly functioning mechanisms of interparliamentary cooperation. Ensuring democratic accountability and parliamentary scrutiny becomes even more important in a moment in which the European Union, following the initial impact of the pandemic, through grants and loans requested by several Member States and assigned on the basis of plans agreed with the Commission and approved by the Council, is even more strongly influencing the national economic policy and encouraging several important and long-awaited (but also long-opposed) reforms at the national level.

Scrutinizing how the goals of the Recovery and Resilience Facility are pursued and how the national reforms are implemented and achieved is the responsibility of not only the European Parliament, nor of each National Parliament individually. Rather, the discharge of these duties requires their joint involvement in interparliamentary cooperation, as the multi-faceted approach of interparliamentary cooperation helps to ensure that all these tasks are better achieved.

* 434 Furthermore, the studies on interparliamentary cooperation in the EU have become rather numerous in the last decade: for example, see B. Crum, J.E. Fossum (eds.), Practices of Interparliamentary Coordination in International Politics: The European Union and Beyond, ECPR Press, Colchester, 2014; C. Hefftler, C. Neuhold, O. Rozenberg, J. Smith (eds.), The Palgrave Handbook of National Parliaments and the European Union, Palgrave, Basingstoke, 2015; N. Lupo, C. Fasone (eds.), Interparliamentary Cooperation in the Composite European Constitution, Hart, Oxford, 2016; F. Lanchester (ed.), Parlamenti nazionali e Unione europea nella governance multilivello, Giuffrè, Milano, 2016; and K. Raube, M. Müftüler-Baç, J. Wouters (eds.), Parliamentary Cooperation and Diplomacy in EU External Relations. An Essential Companion, Edward Elgar, Cheltenham, 2019.

* 435 On the novelties of this conference see, among others, F. Fabbrini, The Conference on the Future of Europe: Process and prospects, in European Law Journal, 2021.

* 436 See, among many, C. Fasone, What Role for Regional Assemblies in Regional states? Italy, Spain and United Kingdom in Comparative Perspective, in Perspectives on Federalism, 2012, 4(1), p. 171 ff.

* 437 B. Crum, J.E. Fossum, The multilevel parliamentary field: A framework for theorizing representative democracy in the EU, in European Political Science Review, 2009, 1(2), p. 249-271.

* 438 By use of the expression “political direction”, I intend to engage the notion that in the Italian constitutional scholarship is labelled “indirizzo politico”: i.e., the way in which the main public policies are designed, in particular between the Executive, the Parliament and of course the citizens, in their role as voters through the general elections. See, among many, V. Crisafulli, Per una teoria giuridica dell'indirizzo politico, in Studi urbinati, 1939, p. 53 ff. See also T. Martines, Contributo ad una teoria giuridica delle forze politiche, Giuffrè, Milano, 1957, p. 162 ff.; E. Cheli, Atto politico e funzione di indirizzo politico, Giuffrè, Milano, 1961, p. 75 ff.; T. Martines, Indirizzo politico, in Enciclopedia del diritto, vol. XXI, Giuffrè, Milano, 1971, p. 134 ff.; M. Dogliani, Indirizzo politico. Riflessioni su regole e regolarità nel diritto costituzionale, Jovene, Napoli, 1985, p. 43 ff.; P. Ciarlo, Mitologie dell'indirizzo politico e identità partitica, Liguori, Napoli, 1988, p. 26 ff.; M. Ainis, A. Ruggeri, G. Silvestri and L. Ventura (eds.), Indirizzo politico e Costituzione. A quarant'anni dal contributo di Temistocle Martines, Giuffrè, Milano, 1998; C. Tripodina, L'“indirizzo politico” nella dottrina costituzionale al tempo del fascismo, in www.rivistaaic.it, 2018, no. 1; A. Morrone, Indirizzo politico e attività di governo. Tracce per un percorso di ricostruzione teorica, in Quaderni costituzionali, 2018, no. 1, pp. 17 ff.; A. de Crescenzo, Indirizzo politico. Una categoria tra complessità e trasformazione, Editoriale scientifica, Napoli, 2020, espec. p. 27 ff.

* 439 B. Crum, J.E. Fossum, The multilevel parliamentary field: A framework for theorizing representative democracy in the EU, cit., p. 264. On the cooperative and competitive dynamics within the field see B. Crum, Patterns of contestation across EU parliaments: four modes of inter-parliamentary relations compared, in West European Politics, 45(2), 2022, pp. 242-261; and A. Herranz-Surrallés, Settling it on the multi-level parliamentary field? A fields approach to interparliamentary cooperation in foreign and security policy, in West European Politics, 45(2), 2022, pp. 262-285.

* 440 On the “Euro-national parliamentary system” cf. C. Fasone, N. Lupo, Conclusion. Interparliamentary Cooperation in the Framework of a Euro-national Parliamentary System, in N. Lupo, C. Fasone (eds.), Interparliamentary Cooperation in a Composite European Constitution, cit., p. 345 ff.; A. Manzella, The European Parliament and the National Parliaments as a System, in S. Mangiameli (ed.), The Consequences of the Crisis on European Integration and on the Member States, Springer, Cham, 2017, p. 47 ff.; N. Lupo, G. Piccirilli, Introduction: the Italian Parliament and the New Role of National Parliaments in the European Union, in N. Lupo, G. Piccirilli (eds.), The Italian Parliament in the European Union, Hart, Oxford, 2017, p. 1 ff. For some criticisms to this formula, see B. Crum, National Parliaments and Constitutional Transformation in the EU, in European Constitutional Law Review, 2017, no. 4, pp. 817-835.

* 441 See R. Ibrido, L'evoluzione della forma di governo parlamentare alla luce dell'esperienza costituzionale dei sei Stati fondatori, in R. Ibrido, N. Lupo (eds.), Dinamiche della forma di governo tra Unione europea e Stati membri, cit., p. 57 ff.; F. Clementi, La V Repubblica francese e il ciclo di razionalizzazioni degli anni Settanta, R. Ibrido, N. Lupo (eds.), Dinamiche della forma di governo tra Unione europea e Stati membri, cit., p. 85 ff.; M. Olivetti, Il regime parlamentare nell'Europa centro-orientale dopo il 1989, R. Ibrido, N. Lupo (eds.), Dinamiche della forma di governo tra Unione europea e Stati membri, cit., p. 113 ff.

* 442 Cf. R. Ibrido, N. Lupo, “Forma di governo” e “indirizzo politico”: la loro discussa applicabilità all'Unione europea, cit., p. 24 ff.

* 443 See E. Griglio, Divided accountability of the Council and the European Council. The challenge of collective parliamentary oversight, in D. Fromage e A Herranz Surrallés (eds.), Executive-Legislative (Im)Balance in the European Union, Oxford, Hart, 2020, pp. 51-66.

* 444 Recently confirmed by the CJEU, in the Chrysostomides case (joined cases C-597/18 P, C-598/18 P, C-603/18 P and C-604/18 P Council v Chrysostomides & Co. and Others ECLI:EU:C:2020:1028). See I. Staudinger, The Court of Justice's Self-restraint of Reviewing Financial Assistance Conditionality in the Chrysostomides Case, in www.europeanpapers.eu, Vol. 6, 2021, No 1, European Forum, Insight of 28 May 2021, pp. 177-188. On the nature of the Eurogroup and on the question of its accountability see: P. Craig, The Eurogroup, power and accountability, in European Law Journal, 23 (3-4), 2017, p. 234 ff.; B. Crum, Parliamentary Accountability in Multilevel Governance: What Role for Parliaments in Post-Crisis EU Economic Governance?, in Journal of European Public Policy, 2018, p. 268 ff.; M. Markakis, Accountability in the Economic and Monetary Union: Foundations, Policy, and Governance, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2020, spec. p. 120 ff.; V.A. Schmidt, Europe's Crisis of Legitimacy. Governing by Rules and Ruling by Numbers in the Eurozone, Oxford, OUP, 2020, spec. p. 123 ff.

* 445 S. Hennette, T. Piketty, G. Sacriste, A. Vauchez, Pour un traité de démocratisation de l'Europe, Paris, Seuil, 2017, and Idd., How to democratize Europe, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, 2019. For a critical discussion of this proposal, see C. Fasone, N Lupo, A. Vauchez (eds), in Parlamenti e democrazia in Europa. Federalismi asimmetrici e integrazione differenziata, Il mulino, Bologna, 2020. See also infra, par. 7.

* 446 The use of the expression `parliamentary diplomacy' has spread widely to identify the tools and procedures used to carry out the fundamental strategies of the `external' activity of parliaments: R. Cutler, The OSCE Parliamentary Diplomacy in Central Asia and the South Caucasus in Comparative Perspective, in Studia Diplomatica, LIX(2), 2006, pp. 79-93; F.G. Weisglas, G. de Boer, Parliamentary Diplomacy, in The Hague Journal of Diplomacy, II(1), 2007, pp. 93-99; L.M. De Puig, International Parliaments, Council of Europe, Strasbourg, 2008, espec. p. 22 ff.; A. Malamud, S. Stavridis, Parliaments and parliamentarians as international actors, in B. Reinalda (ed.), The Ashgate Research Companion to Non-State Actors, Routledge, London, 2011, pp. 101-115.

* 447 I have tried to make this argument in E. Griglio, N. Lupo, Inter-parliamentary Cooperation in the EU and outside the Union: Distinctive Features and Limits of the European Experience, in Perspectives on Federalism, Vol. 10, issue 3, 2018, p. 57 ff.

* 448 N. Lupo, E. Griglio, The Conference on Stability, Economic Coordination and Governance: Filling the Gaps of Parliamentary Oversight in the EU, in Journal of European Integration, XL(3), 2018, pp. 358-373.

* 449 T. Christiansen, E. Griglio, N. Lupo, Making representative democracy work: the role of parliamentary administrations in the European Union, in The Journal of Legislative Studies, 27(4), 2021, pp. 477-493

* 450 T. Christiansen, A.L. Högenauer, C. Neuhold, National parliaments in the post-Lisbon European Union: Bureaucratization rather than democratization?, in Comparative European Politics, 12(2), 2014, pp. 121-140. See also T. Winzen, Bureaucracy and Democracy: Intra-Parliamentary Delegation in European Union Affairs, in Journal of European Integration, 2014, Vol. 36, No. 7, pp. 677-695.

* 451 For the remark that the EWM has a marginal impact on EU policymaking and has drawn more attention to bureaucrats and academics than to national MPs, see T. Raunio, Les parlements nationaux sont-ils mal conseillés? Examen critique du Mécanisme d'alerte précoce, in Revue internationale de politique comparée, 20(1) 2013, pp. 73-88; T. Raunio, T. Winzen, Redirecting national parliaments: Setting priorities for involvement in EU affairs, in Comparative European Politics, Vol. 16, 2, 2016, pp. 310-329.

* 452 See N. Lupo, Un governo “tecnico-politico”? Sulle costanti nel modello dei governi “tecnici”, alla luce della formazione del governo Draghi, in Federalismi, n. 8, 24 marzo 2021, p. 134 ff.

* 453 See, with different approaches to the role of the Speakers' Conference, C. Fasone, Ruling on the (Dis-)Order of Interparliamentary Cooperation? The EU Speakers' Conference, in Interparliamentary Cooperation in the Composite European Constitution, cit, p. 269 ff., and I. Cooper, The Emerging Order of Interparliamentary Cooperation in the Post-Lisbon EU, in D. Jancic (ed.), National Parliaments after the Lisbon Treaty and the Euro Crisis: Resilience or Resignation?, Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2017, p. 227 ff.

* 454 See C. Fasone, N. Lupo, Conclusion. Interparliamentary Cooperation in the Framework of a Euro-national Parliamentary System, in Interparliamentary Cooperation in the Composite European Constitution, cit., p. 345 ff., espec. p. 355 ff.

* 455 See E. Griglio, N. Lupo, The Conference on Stability, Economic Coordination and Governance: Filling the Gaps of Parliamentary Oversight in the EU, in Journal of European Integration, 2018, vol. 40, n. 3, pp. 358-373.

* 456 Among many, see E. Nanopoulos, F. Vergis, The Inherently Undemocratic EU Democracy. Moving beyond the `Democratic Deficit' Debate, in The Crisis behind the Eurocrisis. The Eurocrisis as a Miltidimensional Systemic Crisis of the EU, edited by E. Nanopoulos, F. Vergis, CUP, Cambridge, 2019, p. 122 s.; J. White, Politics of last resort. Governing by emergency in the European Union, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2020, spec. p. 64 s.

* 457 For these hypotheses, see B. De Witte, The law as tool and constraint of differentiated integration, EUI RSCAS Working Papers, 2019, n. 47. On the latest trends of differentiated integration, see also the other working papers of the Horizon 2020 project: Integrating Diversity in the European Union (InDivEU), published in the same series.

* 458 See Art. 24 of the Aachen Treaty, according to which “Un membre du gouvernement d'un des deux États prend part, une fois par trimestre au moins et en alternance, au conseil des ministres de l'autre État”. See Art. 11, par. 6, of the Quirinale Treaty, according to which “Un membro di Governo di uno dei due Paesi prende parte, almeno una volta per trimestre e in alternanza, al Consiglio dei Ministri dell'altro Paese”.

* 459 See the “Résolution no. 241, adoptée par l'Assemblée nationale le 11 mars 2019, relative à la coopération parlementaire franco-allemande”.

* 460 See the “Protocole de Coopération entre l'Assemblée Nationale de la République Française et la Chambre des Députés de la République Italienne”, signed in Paris, 29th November 2021.

* 461 See E. Griglio, N. Lupo, Towards an Asymmetric European Union, Without an Asymmetric European Parliament, Luiss Guido Carli School of Government Working Paper No. 20/2014, June 20, 2014 (Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2460126 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2460126).

* 462 For a contrasting experience, as its composition also included the Member States which did not sign that Treaty, notwithstanding the wording of Article 13 of the Fiscal Compact, see E. Griglio, N. Lupo, The Conference on Stability, Economic Coordination and Governance, cit., p. 362 ff. and D. Fromage, European Economic Governance and Parliamentary Involvement: Some Shortcomings of the Article 13 Conference and a Solution, in Le Cahiers Européennes de Sciences Po, 2016.

* 463 See Art. 330 TFEU according to which “All members of the Council may participate in its deliberations, but only members of the Council representing the Member States participating in enhanced cooperation shall take part in the vote”.

* 464 See N. Lupo, A New Parliamentary Assembly for the Eurozone: A Wrong Answer to a Real Democratic Problem?, in europeanpapers.eu, 2018, n. 1, p. 83 ff.

* 465 In this respect, see A. Manzella, Notes on the “Draft Treaty on the Democratization of the Governance of the Euro Area”, ivi, p. 93 ff.

* 466 See L. Bartolucci, C. Fasone, C. Kelbel, N. Lupo, J. Navarro, Representativeness and effectiveness? MPs and MEPs from opposition parties in inter-parliamentary cooperation, in RECONNECT Working Paper on Interinstitutional Relations in the EU, edited by C. Kelbel, J. Navarro, 28 October 2020, pp. 54-81.

* 467 On the “questions of visibility, sustainability and practicability” posed by the “growing number of forums for inter-parliamentary cooperation” see, for instance, D. Fromage, Increasing Inter-Parliamentary Cooperation in the European Union: Current Trends and Challenges, in European Public Law, 22(4), 2016, pp. 749-772, spec. 769 s.